Dylan’s Electric Shock: An Insider’s View of the 1965 Newport Folk Festival

The 1965 Newport Folk Festival remains etched in music history, not just as a gathering of folk luminaries, but as the stage for a seismic shift in popular music. It was the moment Bob Dylan plugged in, trading his acoustic guitar for an electric Stratocaster, unleashing a performance that polarized audiences and arguably birthed folk-rock. For keyboardist Barry Goldberg, thrust unexpectedly into the center of this storm, the festival was a whirlwind journey from crushing disappointment to becoming part of a legendary, controversial moment. His firsthand account offers a unique perspective on the chaos, creativity, and cultural clash that defined that fateful weekend.

Arrival and Disappointment: A Dream Turns Sour

Rolling into Newport, Rhode Island, on that Thursday felt like stepping into a vibrant musical dream for Barry Goldberg. It was his first trip away from Chicago with the acclaimed Paul Butterfield Blues Band, and the atmosphere was electric – literally and figuratively. The picturesque setting buzzed with musicians and fans, a stark contrast to the smoky blues clubs Goldberg was used to. He quickly noted his Chicago jazz attire – tapered pants and pointed shoes – felt out of place amidst the sea of denim and sandals, epitomized by a fleeting glimpse of Joan Baez running barefoot through the fields.

Despite the minor fashion faux pas, Goldberg’s excitement was palpable. The festival represented a major opportunity for the Butterfield Band. However, this dream quickly soured during rehearsal. Paul Rothschild, the Elektra Records A&R man set to produce the band’s debut album, delivered a devastating blow. “I don’t hear keyboards with the band,” Rothschild declared to Paul Butterfield, looking directly at Goldberg. “I don’t want him here.” Just like that, Goldberg was out – no gig, stranded far from home, his elation replaced by utter devastation.

Unable to afford a ticket home, Goldberg was forced to linger in Newport, waiting to catch a ride back with the bandmates who were now proceeding without him. He describes feeling miserable and isolated amidst the festival’s joyful energy, wandering in a daze caused by the sudden rejection. The vibrant dream had become a personal nightmare.

A Chance Encounter: Dylan’s Electric Ambition

The fog of disappointment began to lift unexpectedly on Saturday night. Goldberg found himself at a party attended by his bandmate, guitarist Michael Bloomfield, and the era’s folk icon, Bob Dylan. Dylan had performed a traditional acoustic set earlier that day, fulfilling audience expectations. But now, he was buzzing with a different idea for his headlining performance on Sunday night – something far removed from the folk purism Newport celebrated.

Goldberg overheard Dylan expressing uncertainty about his backing musicians. “Al Kooper was supposed to come,” Dylan mentioned to Bloomfield, “but I don’t know for sure that he’ll be here, and I might need a band.” Seizing the moment, Bloomfield introduced Goldberg. “Barry’s a great keyboard player,” he told Dylan, suggesting, “Hey, why don’t you use the Butterfield Band to back you up?” Dylan agreed it was a “great idea.”

Shared Roots and Rock ‘n’ Roll Hearts

While Goldberg wasn’t initially a devotee of Dylan’s earlier protest folk, the recently released single “Like A Rolling Stone” resonated differently. He recognized a kindred spirit – Dylan, like Goldberg and Bloomfield, was fundamentally a rock and roller, raised on Gene Vincent, Little Richard, and Buddy Holly. This shared musical DNA transcended genre boundaries.

There was also a cultural and even stylistic connection. Goldberg, Bloomfield, and Dylan were all Jewish guys from the Midwest, sharing similar backgrounds and attitudes. Goldberg even noted Dylan was wearing the same style of tapered pants and pointed boots. Dylan sensed they weren’t folk idealists placing him on a pedestal; they were musicians ready to play, even if it meant bringing electric rock to a folk festival stage. Bob asked Goldberg directly, “Would you like to play with me?” Goldberg’s response was immediate: “Are you kidding? Of course!” In an instant, the Newport nightmare transformed back into a dream. Dylan was assembling his “gang,” and Goldberg was in.

Rehearsal Chaos and Brewing Controversy

The soundcheck the following afternoon was electric in every sense. Goldberg felt the magic as Dylan steered towards uncharted musical territory. A symbolic moment occurred when Dylan began playing Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” on the organ, with Goldberg joining in. It felt like a nod to his folk roots, even as the stage filled with electric instruments – a signal of departure and radical change.

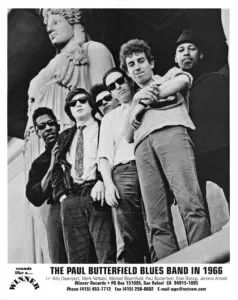

Setting the Stage: The Electric Lineup

The impromptu band consisted of Bloomfield on guitar, Goldberg on piano, and Jerome Arnold (bass) and Sam Lay (drums) from the Butterfield Band. Al Kooper did arrive during the soundcheck, adding organ to the mix – an unusual keyboard pairing at the time that would later be popularized by groups like The Band. They ran through the planned set: “Maggie’s Farm,” “Like A Rolling Stone,” and “Phantom Engineer” (later retitled “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry”).

A snag emerged with “Like A Rolling Stone,” as blues bassist Jerome Arnold struggled with the song’s changes. Al Kooper volunteered to play bass for that number, with Goldberg shifting to the organ. This spontaneous adjustment highlighted the fluid, seat-of-the-pants nature of the endeavor. Dylan, clad in a distinctive polka-dot shirt, remained coolly in control amidst the improvisation.

The rehearsal wasn’t just musically intense; it was fraught with tension. Peter Yarrow of Peter, Paul and Mary, a festival board member and the evening’s emcee, repeatedly yelled at the band to lower their volume. Goldberg recalls Bloomfield glaring back, silently promising defiance. Bloomfield harbored disdain for what he saw as the pretentious, pseudo-intellectual folk establishment, with Yarrow as its embodiment. Simultaneously, Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman, engaged in a physical altercation with Alan Lomax, the famed folklorist who vehemently opposed electric music at the festival. The sight of these two influential figures literally wrestling on the ground, combined with Yarrow’s protests, underscored the battle lines being drawn. It solidified a sense of mission among the musicians, with Dylan as their leader against the resistant folk guard.

The Performance That Shook Folk Music

Taking the stage that night, Goldberg felt terrified. Performing for thousands at a major festival was a world away from the intimate clubs he knew. Yet, as soon as the lights hit and Dylan emerged, clad in black with his Fender Stratocaster, the fear transformed. The image itself was a statement. Goldberg felt the weight and significance of the moment.

Cheers, Boos, and a Defining Moment

Contrary to popular myth, Goldberg recalls hearing both cheers and boos from the outset. He perceived that many detractors weren’t truly listening but reacting viscerally to a perceived betrayal – Dylan turning his back on the folk movement. Their anger overshadowed the music itself. For them, this electric set signified the end of an era. While Dylan was closing one chapter, Goldberg recognized he was simultaneously opening another: the dawn of folk-rock.

From the stage, “Like A Rolling Stone” felt particularly strong, anchored by Kooper’s bassline and Dylan’s cool vocal delivery. During “Maggie’s Farm,” Bloomfield responded defiantly to the boos by cranking his amplifier, unleashing fiery rock and roll licks. Goldberg acknowledges hearing later about Pete Seeger allegedly trying to cut the power lines with an axe due to the volume (a story often debated, with Goldberg noting Dylan’s vocals were actually clear on recordings), but his focus remained on the performance. Bloomfield might have been loud, but they were musical “warriors” backing their leader.

After their brief, three-song electric set, the cacophony of cheers and boos intensified. Peter Yarrow coaxed Dylan back onstage for an acoustic finale (“Mr. Tambourine Man” and “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”). But Goldberg and the band didn’t linger. They had made their statement. Walking offstage, Goldberg felt like a hero, part of a momentous leap into the musical unknown. He sensed that fate had intervened, transforming his personal disaster into participation in a pivotal event in music history.

A Legacy Forged in Controversy

The 1965 Newport Folk Festival remains a touchstone event, largely due to Bob Dylan’s controversial electric performance. Barry Goldberg’s experience provides a compelling ground-level view: the initial personal setback, the serendipitous recruitment by Dylan, the chaotic energy of the rehearsals, and the intense mixture of defiance and artistic purpose during the legendary set itself. While the immediate reaction was deeply divided, the event undeniably altered the trajectory of folk and rock music, marking a point of no return. Goldberg’s unexpected journey from rejected sideman to key player in this historic moment underscores the unpredictable and transformative power of music.