The Unstoppable Force: Exploring the Essential Little Richard Music

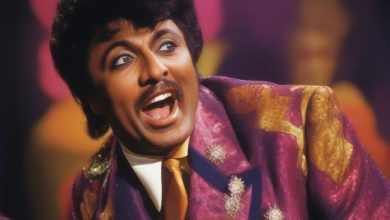

What remains to be said about Little Richard that he hasn’t already articulated better himself? “I am the innovator! I am the originator! I am the emancipator! I am the architect! I’m rock & roll!” he declared to an interviewer, adding, “Now I am not saying that to be vain or conceited.”

Indeed, Little Richard — born Richard Penniman in Macon, Georgia, in 1932 — was merely stating facts. His impact on music is immeasurable. The Beatles modeled their ecstatic falsetto shouts after him; James Brown credited him as “the first to put the funk in rhythm.” Bob Dylan famously noted in his yearbook that his ambition was “to join Little Richard,” and a nine-year-old David Bowie purchased a saxophone with the same hope. The glam rock era spearheaded by Bowie, Mick Jagger’s distinctive stage presence, and Prince’s psychosexual artistry are difficult to conceive without Richard’s pioneering androgynous flamboyance. The landscape of Little Richard Music fundamentally altered popular culture.

Little Richard stood out as the most audacious among the rock & roll giants. His raw sexual expressiveness lacked the down-home charm of Elvis Presley, the clever wit of Chuck Berry, the menacing intensity of Jerry Lee Lewis, the pop sensibilities of Buddy Holly, or the friendly warmth of Fats Domino. Richard’s signature feral woo merged spiritual fervor with orgasmic release, permanently changing how musicians conveyed desire. As Jimi Hendrix aptly put it, “I want to do with my guitar what Little Richard does with his voice.”

“Tutti-Frutti” (1955)

A-wop-bom-a-loo-mop-a-lomp-bom-bom. Little Richard crafted perhaps the greatest (or first) rock & roll lyric to describe a drum fill he envisioned. Alternatively, depending on when asked, it was his retort to his boss while washing dishes at the Macon Greyhound station. Recognizing a potential hit in the raw number Richard hammered out during a recording break, producer Bumps Blackwell enlisted songwriter Dorothy LaBostrie to refine the original lyrics, which explicitly celebrated “good booty” and offered practical advice on anal sex (“If it don’t fit, don’t force it/You can grease it, make it easy”). Though “Tutti-Frutti” was toned down from “explicit” to “suggestive,” Richard’s lustful, tumbling onomatopoeia conveyed a carnal joy far beyond conventional language – the final syllables practically echo the sound of bodies colliding.

“Long Tall Sally (The Thing)” (1956)

While “Tutti Frutti” reveled in lascivious nonsense, its successor “Long Tall Sally” charged ahead with potent innuendo. Little Richard observes Uncle John sneaking Sally through an alley and threatens to tell Aunt Mary, but his delivery makes it clear he sides with the clandestine couple, not the moralizer. The exact nature of their activities remains ambiguous, but the secrecy and Sally’s bald head imply something illicit, even unconventional – not a place for the “good guys.” This untamed energy secured Richard his first R&B chart-topper and his first Top 10 pop hit, proving irresistible to generations of rockers, notably The Beatles. John Lennon recalled, “When I heard it, it was so great I couldn’t speak,” while Paul McCartney meticulously studied it, making it a standout performance piece in the Fab Four’s early days.

“Slippin’ and Slidin’” (1956)

“Another cat put ‘Slippin’ and Slidin” out before I did, Eddie Bo, and it was a hit by him in New Orleans,” Richard explained to Rolling Stone in 1970. “They put mine out the following week, and it killed him, because he didn’t have the rhythm, you see, he didn’t have that thing I have.” Comparing Richard’s rock & roll inferno to Bo’s smoother New Orleans R&B shuffle (titled “I’m Wise”) highlights Richard’s distinctive “thing” – his je ne sais woo. While pianists like Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry sideman Johnnie Johnson might have displayed more melodic ingenuity, Little Richard’s percussive keyboard attack was essential to his sound, handling the heavy rhythmic load and allowing master drummer Earl Palmer to add intricate flourishes beneath.

“Ready Teddy” (1956)

“Ready, set, go man go.” The opening line acts as a starting pistol, with Richard’s voice signaling the race’s start, propelling singer and musicians alike towards the chorus’s end. Each verse is essentially an a cappella shout punctuated by percussive bursts, building anticipation towards the chorus’s sexual excitement. This makes Richard’s claim of merely heading to a sock hop sound like a convenient excuse for less wholesome plans. John Marascalco and Robert Blackwell “brought me the words and I made up the melody and at the time I didn’t have sense enough to claim so much money, because I really made them hits,” Richard told Rolling Stone in 1970. “I didn’t get the money, but I still have the freedom.”

“Heeby-Jeebies” (1956)

Little Richard’s songs defined rock & roll’s dedication to speed, embodying the accompanying optimism, enthusiasm, and restlessness. Yet, on this frantic track (distinct from the Louis Armstrong classic), Richard seems to sing faster than the beat itself, as if his need for acceleration is uncontrollable – fitting, as he laments the “jinx” his “bad luck baby” has cast upon him. It’s fitting that Otis Redding, one of the rawest Sixties soul greats who cited Richard as “my inspiration” and even performed with Richard’s band, The Upsetters, launched his career performing “Heeby-Jeebies” at a talent show, winning it for 15 consecutive weeks.

“All Around the World” (1956)

Little Richard defined “rock & roll” simply as fast R&B: “Played uptempo, you call it rock & roll; at a regular tempo, you call it rhythm & blues.” “All Around the World,” with its jumpy, light rhythm and horn-driven arrangement, stands out rhythmically from Richard’s more frantic hits. Though slightly slower, it’s no less exuberant and undeniably rock & roll. By 1956, the message “Rock & roll is here to stay” was common, but “All Around the World” raised the stakes, insisting the new sound was a global phenomenon – a claim Richard would soon substantiate by touring as far as Australia.

“The Girl Can’t Help It” (1956)

Typically, Little Richard’s vocal power needed no backup; he could carry the weight of an entire quartet. “The Girl Can’t Help It” serves as the exception proving this rule. On the title track for the 1956 Jayne Mansfield film, Richard engages in a call-and-response with backing singers, shouts that amplify the frenzy of this two-and-a-half-minute musical catcall. The beat swings – acknowledging its initial allocation to Fats Domino – but Richard pushes his vocals to the limit. This full-throated wail imbues the record with an air of unbridled sexuality, a hallmark of Little Richard Music.

“Rip It Up” (1956)

An implied violence lurks within the title “Rip It Up,” Little Richard’s second R&B chart-topper. Despite this promise of chaos, the track actually offers some breathing room. Richard doesn’t scream the vocal; instead, he floats his falsetto on the chorus. The band swings effortlessly, creating a single that genuinely grooves. His contemporaries approached it differently – Elvis Presley’s version rocked harder, The Everly Brothers transformed it into a hop – but Little Richard’s swing demonstrates his mastery of jump blues, an appealing trait for a rocker typically operating at maximum intensity.

“Send Me Some Lovin’” (1957)

Little Richard’s undeniable impact on rock & roll sometimes overshadows his contribution to the development of soul music. “He has done so much for our music,” Sam Cooke stated in 1962, and Otis Redding was an equally devoted fan. Comparing Richard’s performance of “Send Me Some Lovin’” to the versions later recorded by these soul legends highlights the diverse paths his influence took. Traces of Richard’s carefully articulated consonants and elaborate vocal flourishes can be heard in Cooke’s smooth delivery. When Richard ramps up the intensity, he seemingly provides a blueprint for the style of passionately ragged pleading that Redding would later perfect.

“Jenny Jenny” (1957)

Without diminishing the dynamic interplay between Lee Allen’s tenor sax and Alvin “Red” Tyler’s baritone, “Jenny Jenny” feels less like a song and more like a marvel of American engineering – a hyperkinetic system designed to deliver the most valuable postwar commodity: Little Richard woos. This sound resonated across the Atlantic to Liverpool. “I could do Little Richard’s voice, which is a wild, hoarse, screaming thing, it’s like an out-of-body experience,” said Paul McCartney, one of Richard’s most adept imitators. “You have to leave your current sensibilities and go about a foot above your head to sing it.”

“Lucille” (1957)

“Lucille” embodies pure frenzy – pounding drums and wailing horns drive their refrain relentlessly. In a guitarist’s hands, this brassy blare would be termed a riff, which is exactly what happened as the song was covered repeatedly by heavy rockers like Status Quo, AC/DC, and The Sonics. It sounded plenty heavy when performed by The Beatles, too. Yet, nothing surpassed the original, thanks entirely to Little Richard, who cries out like a man possessed by carnal desire that, despite his begging and pleading, he knows will remain unfulfilled. This raw emotion is central to the appeal of Little Richard music.

“Keep A-Knockin’” (1957)

John Bonham borrowed Earl Palmer’s intro to “Keep A-Knockin’” for Led Zeppelin’s “Rock and Roll,” implicitly acknowledging that this 1957 single is rock & roll. Ostensibly an answer song to Smiley Lewis’s relaxed 1955 shuffle “I Hear You Knockin’,” “Keep A-Knockin’” is pure noise. After Palmer launches into a hard-driving shuffle, Little Richard yells for his unwanted guest to leave. From there, it becomes a contest between Richard and his saxophonist to create the loudest possible sound. Rock & roll rarely sounded louder, better, or more pure than this.

“Good Golly, Miss Molly” (1958)

Echoing T.S. Eliot’s observation that mature artists steal rather than imitate, Little Richard adopted a catchphrase used by Southern DJ Jimmy Pennick for his song title and borrowed Ike Turner’s piano intro from Jackie Brenston’s “Rocket 88.” “I always liked that record,” Richard recalled, “and I used to use the riff in my act, so when we were looking for a lead-in to ‘Good Golly, Miss Molly,’ I did that and it fit.” Nevertheless, “Good Golly, Miss Molly” sounds unmistakably like Little Richard. His voice pushes into the red on every line, and each exclamation of the title sounds spontaneously conceived.

“Ooh! My Soul” (1958)

“Elvis may be the King of Rock & Roll,” Little Richard once proclaimed, “But I am the Queen.” He could be evasive or candid about his sexuality, sometimes simultaneously – “I believe I was the founder of gay,” he told John Waters, while confirming nothing specific. Yet, from his towering pompadour and mascara-enhanced eyes to his orgasmic whoops and non-masculine physical energy, Richard was an undeniable pioneer of rock & roll androgyny. “Ooh! My Soul” might be his most flirtatiously gender-bending performance on record. He charges through verses like a showboating running back, then squeals the title like a coy cheerleader. “Ooh! My Soul” captures the sound of Little Richard seducing himself, its post-climactic giggle confirming his own irresistible charm.

“Kansas City”/”Hey Hey Hey Hey” (1959)

Little Richard recorded two versions of the Leiber/Stoller classic in 1955. The initial, more conventional take closely follows Little Willie Littlefield’s original recording. On the later version, however, he infuses the song with his personality, breaking into a “hey hey hey hey” shout echoed by an enthusiastic chorus. Before this second take was released in 1959 (concurrently with Wilbert Harrison’s hit version), Richard recorded a song titled “Hey Hey Hey Hey,” about returning “back to Birmingham,” featuring the same introductory seven-note guitar lick and drum roll as “Kansas City.” This is how Little Richard not only transformed “Kansas City” into a signature piece but also earned royalties when The Beatles covered it.

“By the Light of the Silvery Moon” (1959)

In 1956, Fats Domino achieved success by reviving old popular songs, notably taking the 1940 tune “Blueberry Hill” high on the R&B and pop charts. Little Richard followed suit in 1959, reaching back 50 years for the Tin Pan Alley standard “By the Light of the Silvery Moon.” His version is lively and nimble, driven by honking horns and an insistent shuffle rhythm. While the rhythm is infectious, the single truly shines through the vocal performance. Grinning and mincing, Richard skirts the edge of camp; he isn’t mocking the beloved standard but gives it a knowing wink.

“Bama Lama Bama Loo” (1964)

“Bama Lama Bama Loo” marks one of Little Richard’s attempts to recapture his earlier magic. After moving between labels in the early Sixties, he returned to Specialty Records in 1964 and released this piece of frenetic nonsense. With its gibberish lyrics and screams, the song clearly aimed to evoke “Tutti Frutti.” While it doesn’t quite reach the same level of wildness due to his age, the ever-astute Richard leverages maturity. He allows the rhythms to slow slightly, settling into a thick, grooving shuffle.

“I Don’t Know What You’ve Got but It’s Got Me” (1965)

Although it didn’t cross over to the pop charts, “I Don’t Know What You’ve Got but It’s Got Me” became Little Richard’s final significant R&B hit in late 1965. Fittingly, the song aligns with Sixties soul sensibilities rather than Fifties R&B. A languid, church-influenced slow-burner (split into two parts for its single release), “I Don’t Know” features Little Richard embracing the deep soul sound emerging from Southern hubs like Stax/Volt. Unsurprisingly, this earthy context brings out Richard’s best. He connects with his gospel roots more profoundly than on his seminal Specialty recordings, demonstrating his ability to testify with powerful passion.

“I Need Love” (1967)

During his mid-Sixties tenure at Okeh Records, Little Richard navigated the evolving landscape of soul music, somewhat isolated from mainstream success. He achieved a minor hit with “Poor Dog (Who Can’t Wag His Own Tail),” but the electrifying “I Need Love” was arguably superior. Despite failing to chart even on the R&B lists, the single features Richard riding an uptempo Southern soul groove reminiscent of Otis Redding. He adapts this vibrant sound, adding a show-business flair as he modulates his delivery, building to cathartically explosive choruses.

“Freedom Blues” (1970)

Like many veteran rock & rollers, Little Richard gained an opportunity to connect with a new audience at the beginning of the Seventies. Signing with Reprise Records in 1970, he chose not to simply recreate his past hits – a path Fats Domino pursued. Instead, Richard plunged into the thick, funky sounds of the era. “Freedom Blues,” with its deep Southern groove, functions as both a civil-rights anthem and a reflection of the paisley-colored times. What stands out is not just Richard’s impassioned performance, but also his skillful integration of counterculture elements into a single that still resonates powerfully today, showcasing the enduring versatility of Little Richard music.