Elvis Presley Thats Alright: The Accidental Spark of Rock and Roll

The story of rock and roll is filled with pivotal moments, but few are as charged with serendipitous energy as the recording of “That’s All Right” by a young, unknown Elvis Presley in 1954. This single session at Sun Records didn’t just launch a career; it arguably ignited a cultural revolution. But the journey to that moment involved a visionary record producer with a unique mission, a shy truck driver brimming with untapped talent, and a spontaneous studio jam that captured lightning in a bottle. Understanding the genesis of Elvis Presley Thats Alright requires looking beyond the singer and exploring the fertile ground prepared by Sam Phillips and the raw, eclectic influences that shaped the future King of Rock and Roll.

Sam Phillips’ Vision and Sun Records’ Genesis

Sam Phillips wasn’t just a record producer; he was a man with a mission. Deeply passionate about the blues and R&B music created by black artists in the segregated South, Phillips believed this music held the power to break down racial barriers. He was convinced that if he could get white audiences to truly listen and connect with the feeling and soul of black music, racism could be diminished. His initial venture, the Phillips label co-founded with DJ Dewey Phillips (no relation), was short-lived. His experiences leasing master recordings of artists like Howlin’ Wolf and B.B. King to labels like Chess and Modern proved frustrating, often resulting in the labels poaching the artists directly.

Determined to maintain control and fulfill his vision, Phillips launched Sun Records in Memphis. He needed a hit, something as impactful as “Rocket 88” (which he had recorded with Jackie Brenston and His Delta Cats and leased to Chess) or an artist as significant as Howlin’ Wolf, whom Phillips considered the greatest talent he ever recorded. Wolf, however, had moved on to Chess Records in Chicago. Phillips lamented that Wolf’s Chess recordings lacked the raw power captured at his 706 Union Ave studio, but the fact remained: Sun needed a star.

An early attempt at generating buzz involved recording an “answer record” to Big Mama Thornton’s hit “Hound Dog”. This was a common practice in R&B. Phillips conceived “Bear Cat,” repurposing the “Hound Dog” melody and slightly altering the lyrics (a practice he believed standard, though it later cost him dearly in a copyright lawsuit from Duke Records). He enlisted local DJ Rufus Thomas for the vocals. “Bear Cat” became a surprising R&B hit, reaching number three, a significant achievement for the fledgling label. However, the lawsuit drained precious resources. Phillips knew he needed something more sustainable, something that could cross the racial divide more effectively. He began to ponder finding a white performer who possessed the same raw feeling and soul he heard in his black artists, hoping this could serve as a bridge for white audiences.

The Unlikely Arrival of Elvis Presley

History walked into the Memphis Recording Service (Sun’s studio) in the form of Elvis Aaron Presley, a nineteen-year-old truck driver from a poor Mississippi family who had moved to Memphis. He came initially to record a demo acetate (“My Happiness” and “That’s When Your Heartaches Begin”) as a gift for his mother. Phillips’ assistant, Marion Keisker, was immediately struck by the young man. She later claimed she recognized him as the “white man who could sing like a black man” that Phillips sought. Phillips himself contested this, claiming the discovery as his own. Listening to those early acetate recordings, predominantly smooth crooning influenced by acts like The Ink Spots, it’s not immediately obvious what sounded so distinctively “black” to Keisker or Phillips.

What Phillips did see, however, was an attitude – specifically, a profound insecurity. Elvis was painfully shy, an introverted country boy often bullied at school, known for his unusual clothes (bought from Lansky’s on Beale Street, frequented by black customers) and tendency to keep to himself, close only to his mother. He absorbed music voraciously from all directions: the country his mother loved (Louvin Brothers), the fiery gospel of his Pentecostal church, the blues he heard on Beale Street, and the smooth harmonies of white Southern Gospel quartets like his idols, the Blackwood Brothers. He dreamt of singing harmony in such a group. He hung around with other local teens like Johnny and Dorsey Burnette and Johnny Black (whose brother Bill played bass), but always remained slightly apart, an outsider. Phillips, who had battled depression himself, recognized this outsider quality, this vulnerability, as something akin to the bearing of the great black artists he admired, men shaped by societal pressures. He saw potential in Elvis’s unique blend of influences and palpable insecurity.

The Session That Ignited Rock and Roll

Phillips decided to pair Elvis with two members of the local country group, the Starlite Wranglers: guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black. Neither were technical virtuosos, which Phillips preferred; they played with feeling. He trusted Moore’s instincts and arranged a rehearsal. Moore wasn’t initially blown away, but sensed something intriguing about the young singer.

Sam Phillips booked a studio session, initially focusing on ballads, the style Elvis seemed most comfortable with. Nothing clicked. They tried song after song without success. During a break, Elvis began spontaneously “fooling around,” playing a sped-up, almost frantic version of Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s 1946 blues number, “That’s All Right Mama.” Black jumped in with his upright bass, slapping the strings, and Moore added guitar licks. Phillips, hearing the energy from the control room, urged them to start again so he could record it.

Arthur Crudup and the Song’s Blues Roots

Arthur Crudup was a Mississippi bluesman known for reworking similar melodic and lyrical themes across his songs. “That’s All Right Mama” itself drew inspiration from blues traditions, including Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “Black Snake Moan” and elements Crudup had used in his own earlier tracks like “If I Get Lucky” and “Mean Ol’ Frisco Blues.” Crudup’s original recording is a classic piece of down-home blues, rhythmic and rooted in the Delta sound.

Elvis Presley’s Transformation of “That’s Alright”

The version Elvis, Scotty, and Bill stumbled upon was radically different. They transformed Crudup’s country-blues into something new – faster, lighter, infused with a nervous energy that bordered on joyous irreverence. Bill Black’s percussive slap bass replaced drums, and Scotty Moore added simple, effective electric guitar fills. It wasn’t precisely “a white man singing like a black man”; it sounded more like an electrified, hyper-caffeinated form of hillbilly music. Yet, Presley’s vocal performance was key. He sang with a playful confidence that belied his shyness and inexperience, sliding between registers, treating the song with a lightness that was distinct from both traditional blues and country. This spontaneous creation, Elvis Presley Thats Alright, captured a unique, uninhibited energy.

Crafting the Sound: “Blue Moon of Kentucky” and Slapback Echo

Needing a B-side, the trio tackled Bill Monroe’s bluegrass waltz, “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” They applied the same energetic, uptempo approach, transforming the mournful country standard into another exhilarating slice of proto-rockabilly. The arrangement was sparse – Elvis’s rhythm acoustic guitar, Black’s driving slap bass, Moore’s electric guitar fills – but glued together by Sam Phillips’ signature production technique: slapback echo.

Phillips achieved this sound using two tape recorders. One recorded the performance directly, while the second played back the signal fractions of a second later, which was then also recorded by the first machine. This created a distinctive, swimming reverberation, particularly potent on vocals, giving Sun recordings a unique sonic identity that other studios struggled to replicate. On both “That’s All Right” and “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” this echo added an atmospheric, almost futuristic dimension to the raw performance.

Radio Debut and the Birth of a Phenomenon

Phillips rushed an acetate of “That’s All Right” to his friend, DJ Dewey Phillips. Dewey was hesitant – it wasn’t the usual R&B fare for his “Red, Hot and Blue” show – but agreed to play it. Elvis, learning his record was about to be broadcast, was so terrified he went to a movie theater to avoid listening. The response was instantaneous and overwhelming. Phones lit up the station switchboard. Dewey played the record repeatedly – reportedly 14 times that night. Elvis’s parents had to fetch him from the cinema for an impromptu on-air interview. Dewey cannily asked Elvis which high school he attended (Humes High), subtly informing the predominantly black audience, many of whom assumed the singer was black, that Elvis was white.

“That’s All Right” became a regional sensation, a significant hit for a small independent label, straddling the lines between country and R&B charts. Tragically, Arthur Crudup, having sold the rights years before, reportedly saw little to no royalties from Presley’s massive hit, a recurring story in music history.

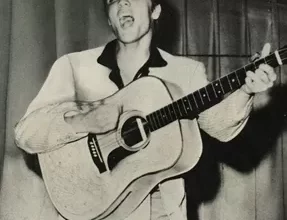

From Stage Fright to Sex Symbol

The studio magic translated unexpectedly to the stage. During their early performances, Presley’s intense stage fright manifested physically. As Scotty Moore recalled, Elvis would start shaking, particularly his legs. Clad in the loose, peg-legged trousers favored by many black men at the time (distinct from the tighter jeans worn by most white youths), this nervous shaking took on an unintentionally provocative, rhythmic quality. The audience, particularly the women, reacted viscerally.

Presley, ever attuned to audience response despite his initial shyness, quickly learned to amplify these movements. The leg-twitching, the hip swivels – born from anxiety – became deliberate signatures. Within a remarkably short time, the awkward, spotty-necked boy transformed. The raw energy captured on elvis presley thats alright found its physical embodiment on stage, and Elvis Presley rapidly evolved from a nervous newcomer into the world’s first rock and roll sex symbol, changing the face of popular music and culture forever.

Conclusion

The recording of “That’s All Right” stands as a watershed moment, born not from a calculated plan but from a confluence of factors: Sam Phillips’ unique vision and technical ingenuity, Arthur Crudup’s foundational blues, the intuitive chemistry between Elvis, Scotty Moore, and Bill Black, and crucially, Elvis Presley’s own paradoxical nature – a shy outsider brimming with diverse musical knowledge and an unconscious charisma. The song itself, a fusion of country speed and blues feeling amplified by studio echo, didn’t neatly fit existing categories but created its own. It was the accidental spark that ignited the rockabilly fire and launched Elvis Presley’s trajectory towards superstardom, proving that sometimes the most revolutionary moments happen when you’re just fooling around. The reverberations of that Memphis session continue to echo through music history.