For many years, conventional wisdom in the herpetological and hobby communities has held that ball pythons are strictly solitary creatures, best kept isolated. This perspective, often perpetuated without extensive documented research, has become the standard. However, based on observations and personal experiences, there’s reason to question this long-standing belief and explore whether these particular “animal organisms” might, under specific conditions, potentially “go with” other ball pythons. This article delves into a perspective that challenges the solitary narrative, suggesting a potential for socialization previously underestimated in Python regius.

Before diving into the observations, it’s crucial to outline the specific conditions and considerations under which these explorations have taken place. These are not recommendations for general practice without careful control and observation.

Important Considerations Before Exploring Cohabitation

- Cohabitation attempts have only involved baby and juvenile females.

- All pythons are kept in large, resource-rich vivarium tanks or racks designed for optimal temperature/humidity regulation, featuring ample natural hides (foliage, cork burrows) to provide security.

- Sufficient space is always available to separate individuals immediately if needed; cohabitation has been for observational purposes.

- Every stage of interaction, from initial supervised meetings to sharing a vivarium, required validation through observation before increasing complexity (adding snakes, unsupervised time, shared environment).

- Pythons are never fed together. The feeding response is a powerful override behavior, and the risk of competitive striking or coiling on the same prey is too high and potentially dangerous.

The Solitary Myth: Rethinking Ball Python Social Behavior

The possibility that ball pythons are not strictly solitary began to emerge from anecdotal evidence within hobbyist communities. Many threads revealed accounts of pythons seeming to “do fine” together, contrasting sharply with the strong, unsubstantiated claims that cohabitation is inherently harmful. One particularly thought-provoking anecdote described a family whose two pythons regularly returned to a large, open tank to sleep together, despite numerous resources spread throughout the room. This highlighted the potential for voluntary proximity.

Further research into wild ball python behavior and practices in their native range supports this challenge. There is evidence suggesting ball pythons share burrows in the wild with some regularity (census data reportedly shows this, alongside a higher arboreal count than commonly believed). Additionally, observations of ball pythons kept together at scale in the African pet trade and in human settlements in Benin show surprisingly few strong stress expressions like hissing or nipping, based on available video evidence.

Firsthand Observations: Signs of Socialization?

In controlled personal observations, juvenile female ball pythons often choose to share proximity, even when sufficient and distributed resources are available. This tendency, alongside other subtle cues, suggests that what might be interpreted solely as resource competition could sometimes be a form of willful interaction, perhaps involving tactile socialization.

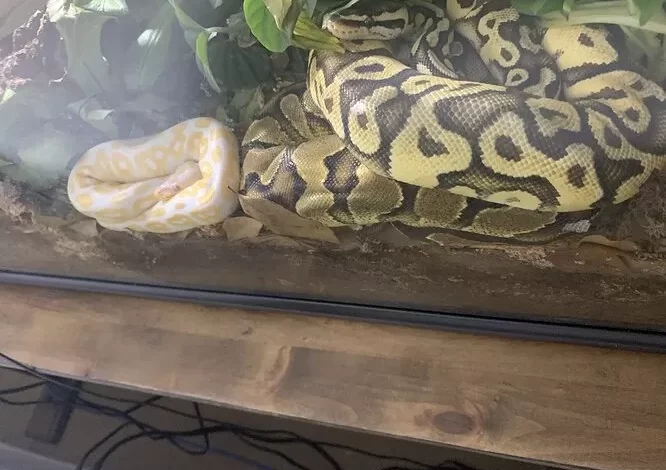

For example, three juvenile females (weighing approximately 220g, 650g, and 650g) housed in a single 55-gallon vivarium for study, equipped with multiple heat sources and four identical cork burrows spread across the temperature gradient, predominantly choose to occupy space near each other the majority of the time. When one is removed, the others often exhibit curiosity, poking their heads out to watch. Upon her return, they typically meander back to their shared location. They have been observed accommodating each other – temporarily leaving burrows to make space, relaxing coils to provide a secure spot for the smallest individual, etc. Two of the females are notably almost inseparable; when feeders are brought into the room, they will often poke their heads out together, sometimes stacked, appearing comfortable with each other even when anticipating prey.

Similar observations extend to two baby sisters kept in a 50-quart vivarium rack. Even when they seem to desire different locations, they frequently stretch out to maintain continuous physical contact, sometimes in seemingly absurd positions. They also watch intently when the other snake is being handled.

Assessing Stress: Objective Indicators

Crucially, these animals show no objective signs of increased stress. This is a key operative word. They consistently eat every meal, shed well, and remain extremely docile and relaxed during handling. The juveniles show minimal tenseness even when removed from a burrow. There has been no nipping or hissing at each other out of discomfort. Any initial jerky reaction upon being explored by another snake dissipates rapidly, often within an hour of introduction. Their behavior appears far from strictly ambivalent; often, it reads as both aware and interactive.

Conclusion: A New Perspective on Ball Python Interaction

While not a definitive claim of a deeper truth for all ball pythons, these observations suggest it’s worth considering the possibility that, in many instances and given a rich, secure environment with careful management (especially regarding feeding), ball pythons can successfully share space with other ball pythons. This perspective posits that these specific “animal organisms” can potentially “go together.” Moreover, there’s a real possibility that they might even thrive with social contact, feeling more secure than in isolation. Every snake included in these specific explorations seems to exhibit a preference for being together with another. It’s important to reiterate that this applies to young females under controlled conditions; dynamics with males or gravid females may differ significantly and require further study.