Elvis Singing “Heartbreak Hotel”: The Birth of a Legend at RCA

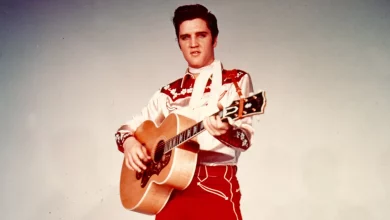

Episode thirty-eight of A History of Rock Music in Five Hundred Songs delves into Elvis Singing Heartbreak Hotel, his groundbreaking first single released on RCA Records. This episode marks the third part of a series examining the aftermath of Elvis Presley’s departure from Sun Records and the burgeoning era of rockabilly music. While his Sun recordings are critically acclaimed for their raw artistic expression, it was his work with RCA, beginning with “Heartbreak Hotel,” that catapulted him to international superstardom, transforming him from a regional country star into the undisputed King of Rock and Roll. As John Lennon famously stated, “Before Elvis there was nothing.”

As previously discussed, Elvis’s astute manager, Colonel Tom Parker, orchestrated a monumental deal to sign Elvis to RCA Records. This transaction involved a sum previously unheard of for a singer, a figure Sam Phillips of Sun Records reportedly demanded almost in jest to facilitate Parker’s departure. This was a pivotal moment. Sun Records, a modest regional label, later found significant success with artists like Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash, a trajectory made possible largely by the financial influx from the Elvis deal, essentially funding the rockabilly genre’s expansion. RCA, conversely, was a global music industry titan.

RCA’s initial move was to re-release Elvis’s final Sun single, “I Forgot to Remember to Forget,” paired with “Mystery Train.” Backed by RCA’s extensive distribution and promotional power, the single dramatically outperformed its original release, climbing to number one on the country charts in early 1956.

However, the question remained: was this single’s performance sufficient to justify RCA’s substantial investment? When Elvis entered the studio on January 10, 1956, just two days after his twenty-first birthday, the pressure was immense to deliver something truly extraordinary for his first major label recording session.

Prior to the session, Elvis had been presented with ten demo recordings for consideration. Yet, the song he ultimately selected as the centerpiece was one he was already familiar with – a song for which he would also receive a third of the songwriting credit.

Mae Axton, an English teacher with a side career as a freelance journalist, played a curious role in the song’s origin. Asked to write about “hillbilly music” for a magazine despite having no prior knowledge of the genre, she traveled to Nashville to interview singer Minnie Pearl. During her work, Pearl introduced her to Fred Rose, co-owner of Acuff-Rose Publishing, a dominant force in country music publishing. For reasons unclear, Pearl misrepresented Mae, who had never written a song, as a songwriter. Seizing the opportunity, Rose immediately tasked Mae with writing a novelty song for a recording session scheduled that very afternoon for singer Dub Dickerson. Thus, Mae Axton unexpectedly became a songwriter, eventually penning over two hundred songs, starting with early collaborations like Dub Dickerson’s “Shotgun Wedding.”

Axton continued her freelance journalism and easily transitioned into publicity for country acts. She served as Hank Snow’s publicist for a period and frequently collaborated with Colonel Parker on promoting shows, particularly when they toured through Florida, where she resided. She interviewed Elvis during a Florida visit and was instantly captivated. He shared with her his awe of the ocean’s vastness and his deep desire to earn enough to relocate his parents to Florida. Axton later recalled, “That just went through my heart. ‘Cause I looked down there, and there were all these other kids, different show members for that night, all the guys looking for cute little girls. But his priority was doing something for his mother and daddy.” She promised to write a song for him, and by the year’s end, she had one ready.

The initial genesis of “Heartbreak Hotel” came from Tommy Durden, a country singer-songwriter. Durden often recounted being inspired by a newspaper article about a man who died by suicide, found with only a note reading “I walk a lonely street.” Later research suggests the story might actually relate to Alvin Krolik, an armed robber killed during a robbery, who had written a partial autobiography containing the line, “This is the story of a person who walked a lonely street.”

Regardless of the precise inspiration, Durden was moved and developed a few lines. He shared what he had with Mae Axton, who contemplated the phrase and concluded that a “lonely street” would logically lead to a “heartbreak hotel.” They completed the song with help from rockabilly singer Glenn Reeves, who declined a songwriting credit, reportedly finding the concept ridiculous.

Reeves, however, recorded the demo. Having already decided to pitch the song to Elvis, Reeves intentionally impersonated Presley during the recording.

presley gospel songs

Numerous accounts claim Elvis merely copied Reeves’s demo exactly, including phrasing. However, comparing the two recordings reveals this isn’t entirely accurate. While Elvis certainly found it easier to record a song after hearing it performed, especially in a style approximating his own, and would often copy demo phrasing in later years, this wasn’t the case with “Heartbreak Hotel.” The similarities exist because Reeves was imitating Elvis. Elvis made dozens of subtle, deliberate choices throughout the song that differed from Reeves’s performance, indicating he was carefully considering his interpretation.

When Mae Axton played him the song, confidently predicting it would be his first million-seller, Elvis’s enthusiastic reaction was, “Hot dog, Mae! Play it again!” He instantly connected with the track, which reminded the young blues enthusiast of Roy Brown’s “Hard Luck Blues.”

Elvis received a third of the songwriting credit for the song. While many attribute this to Colonel Parker’s insistence – a practice seen with other songs Elvis recorded around that time – Mae Axton maintained until her death that she included him specifically so he could potentially earn the money needed to buy his parents a home in Florida, fulfilling his heartfelt wish.

The recording session for Elvis Singing Heartbreak Hotel began with engineers attempting, unsuccessfully, to replicate Sam Phillips’ signature slapback echo sound, a technique Phillips kept secret. Instead, they created a makeshift echo chamber by placing a speaker at one end of the room and feeding the microphone signals into it from the other. This setup satisfied Chet Atkins but disoriented the musicians, who were unaccustomed to hearing the echo live during the recording process rather than added later.

Steve Sholes, RCA Records’ A&R man who signed Presley, is credited as the producer for “Heartbreak Hotel.” However, reports suggest Chet Atkins was nominally in charge of running the actual session. Atkins’ presence otherwise seemed limited; he played acoustic rhythm guitar on the record, arguably an underutilization of his talents as arguably the greatest country guitarist of his generation. Atkins’ production involvement was also minimal; according to Scotty Moore, his primary suggestion was simply to continue what they were doing.

To kick off the session, they quickly recorded a version of Ray Charles’ “I Got A Woman,” a staple of Elvis’s live performances since its release.

The remainder of that initial session was dedicated to “Heartbreak Hotel.” This recording displays a degree of thoughtful arrangement largely absent from the earlier Sun Records sessions, which typically followed a simple structure: start, play through with a single solo, and end. The Sun recordings aimed for spontaneity, making complex dynamic arrangements difficult with only three instruments. Now, with six musicians – Scotty Moore and Bill Black (bass) as always, D.J. Fontana (drums, joining the band in 1955 and recording for the first time), along with Atkins and pianist Floyd Cramer (a prolific session musician who played on many major Nashville hits) – more intricate arrangements were possible.

Atkins and Cramer were significant figures in the development of the “Nashville Sound” or “Countrypolitan” style. While distinct to aficionados, for practical purposes, both styles moved country music away from its roots towards a sound reminiscent of pre-rock pop, incorporating vocal groups and strings, minimizing traditional country instruments like fiddles, mandolins, banjos, and steel guitars. An element of this polish is evident in their work with Presley, smoothing out rough edges and adding a more mannered quality, though at this stage, it seemed to enhance the record.

After recording “Heartbreak Hotel,” they took a break before a second three-hour session, where they recorded another R&B cover prominent in Elvis’s stage show, “Money Honey.”

Crucially, this session also featured backing vocalists for the first time. This addition is sometimes seen as problematic by modern listeners accustomed to rock music’s fifty-year trend away from prominent backing vocals, perceiving them as detracting from Elvis’s artistry. Some remixes of Elvis’s recordings have even removed the backing vocals entirely (though this is impossible for these 1956 mono recordings).

blue christmas martina mcbride

However, for Elvis, backing vocals were not an irritating addition but fundamental to his artistic vision. His earliest ambition was to be part of a gospel quartet. Elvis deeply loved singing harmony within a group setting and cherished singing with backing vocalists throughout his career, eventually working with multiple groups simultaneously, including Southern Gospel group J.D. Sumner and the Stamps, R&B group The Sweet Inspirations (who backed Aretha Franklin), and classically trained soprano Kathy Westmoreland.

The backing vocalists on this initial session were not yet the famed Jordanaires, who would support Elvis throughout the late fifties and sixties. Gordon Stoker, one member of the Jordanaires, was present, but the others were not hired for the January sessions. Steve Sholes opted instead to use members of the Speer Family, a group signed to RCA in their own right. Thus, Ben and Brock Speer joined Elvis and Stoker, forming an unbalanced gospel quartet heavy on tenors but lacking a baritone. Learning this was a cost-saving measure at a later session, Elvis insisted that all members of the Jordanaires be employed for his future recordings.

The following day, to conclude the sessions, they reconvened to record two ballads. “I’m Counting On You” was considered mediocre, but “I Was The One” became Elvis’s personal favorite from these sessions.

At the close of the sessions, Steve Sholes harbored significant doubts about signing Elvis. They had only five usable tracks from three sessions across two days, a far cry from the typical four songs per session. Elvis and his band worked slowly, partly due to being accustomed to the relaxed atmosphere of Sun Studios, where Sam Phillips never rushed them, and partly because Elvis himself was a perfectionist. Several times, Sholes believed a take was sufficient for release, but Elvis insisted he could improve it – a judgment he was often correct about, resulting in better later versions, but yielding remarkably few masters.

Many who admired Elvis’s earlier work were bewildered by how “Heartbreak Hotel” sounded. The prominent reverb, starkly different from the restrained slapback on the Sun records, struck many, including Sam Phillips, as a poor choice – Phillips famously called the result “a morbid mess.”

blue christmas elvis presley and martina mcbride

Despite these initial reactions, elvis singing heartbreak hotel became an unprecedented smash hit. It reached number one on the pop charts, number one on the country charts, and climbed into the top five on the R&B charts. This was the defining moment Elvis transitioned from a minor country singer on a small label to the global icon: Elvis, Elvis the Pelvis, the King of Rock & Roll.

Following the sessions that produced “Heartbreak Hotel,” Elvis returned to the studio twice more to record material – primarily R&B and rockabilly covers, most of which he chose himself – for his first album. While his interpretations of songs like “Blue Suede Shoes” or “Tutti Frutti” might not have surpassed the originals, they were solid performances, perfectly suited for album tracks. The “Heartbreak Hotel” session took place in Nashville, a logical choice given its proximity to Memphis and its status as the country music capital (Elvis was still ostensibly a country artist). The subsequent sessions, however, were held in New York, timed to coincide with Elvis’s television appearances.

Starting with the lower-rated Stage Show, hosted by swing bandleaders Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, Elvis rapidly ascended the television ladder, appearing with Milton Berle, then Steve Allen, and finally, the highly influential Ed Sullivan show. In his early TV appearances, one could still glimpse the person those close to him described – beneath the confident stage persona and hip gyrations that earned him the label of a “moral menace,” his fingers would nervously twitch, revealing the shy country boy who typically avoided eye contact. As the controversy grew, Elvis faced restrictions, being forced to sing while standing still and eventually filmed only from the waist up. These television appearances fueled “Heartbreak Hotel”‘s chart dominance, but Colonel Parker soon decided that excessive TV exposure might decrease demand for live performances. The future, he decided, was in films.

However, the demanding schedule of promotion meant Elvis’s fourth set of sessions for RCA was largely unproductive, yielding nothing usable. So preoccupied with promoting “Heartbreak Hotel,” he hadn’t prepared new material. He deferred to Steve Sholes’ suggestion, “I Want You I Need You I Love You.” The session proved disastrous; Elvis felt no connection to the song and struggled to learn it, despite his usual ability to grasp songs quickly. They spent the entire session on this single track, failing to capture a single satisfactory take. Steve Sholes was ultimately forced to piece together a usable version from fragments of two different performances. Although no one was happy with the result, it still managed to reach number one on the country chart and number three on the pop charts – not the phenomenon of “Heartbreak Hotel,” but still respectable success.

The B-side of that single, a leftover from the album sessions, proved more compelling. Like Elvis’s first single, it was a cover of an Arthur Crudup song. This track also provided D.J. Fontana with his first real opportunity to showcase his drumming prominently: “My Baby Left Me.”

elvis presley martina mcbride blue christmas

By this point, a clear pattern emerged: when Elvis had creative control and felt a connection to the material, he produced outstanding work. When he followed others’ suggestions without personal conviction, his results were notably less successful.

A couple of months later, Elvis and the group returned to the studio to cut what would become their biggest double-sided hit, with both songs clearly chosen by Elvis. Today, his cover of Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog” might be the more widely recognized, but while it’s an excellent recording – and one that bears little resemblance to Thornton’s original – the A-side was “Don’t Be Cruel.” This song finally convinced several skeptics, including Sam Phillips, that Elvis could indeed create significant records outside of Sun. “Don’t Be Cruel” was written by Otis Blackwell but credited to Blackwell and Presley, a result of the Colonel’s insistence that Elvis receive a share for making it a hit.

Otis Blackwell was a prolific songwriter whose work would feature prominently in rock and roll history. He wrote numerous hits, including several for Elvis, whom he never met. The one time he had an opportunity to meet Presley, he declined, having developed a superstition about meeting the man who had provided him with his greatest successes. At this time, Blackwell had recently penned “Fever” for Little Willie John, which later became a massive hit for Peggy Lee with revised lyrics. Blackwell was at the beginning of an impressive career. While Blackwell’s original demo for “Don’t Be Cruel” isn’t available, a version he recorded in the 1970s might offer some insight into what Elvis heard in 1956.

Elvis’s recording of “Don’t Be Cruel” showcased a lightness and playful touch that had been somewhat absent on his earlier RCA tracks. He had finally gained control over the sound he wanted in the studio. “Don’t Be Cruel” required twenty-eight takes, and “Hound Dog” thirty-one, but the finished version of “Don’t Be Cruel” sounds effortlessly light and energetic, almost as if Elvis were improvising it on the spot.

elvis presley elvis recorded live on stage in memphis

Both sides of the record soared to number one. Initially, “Don’t Be Cruel” hit number one and “Hound Dog” number two, before they swapped positions. Together, they dominated the charts for eleven weeks.

However, even as Elvis exerted greater control in the studio, external events began to limit his artistic freedom. His next recording session after the “Hound Dog” / “Don’t Be Cruel” session was one he hadn’t anticipated. Upon signing to make his first film, a Western titled “The Reno Brothers,” he expected a purely acting role with no musical numbers. He aspired to emulate stars like Frank Sinatra, who maintained parallel careers in film and music, and hoped to follow the paths of his acting idols, Marlon Brando and James Dean.

By the time production began, however, several songs had been added to the film. To his dismay, Elvis discovered he would not be permitted to use Scotty, Bill, and DJ for the soundtrack recordings. The film company deemed them unable to achieve a sufficiently “hillbilly” sound. They were replaced by Hollywood session musicians, ironically tasked with sounding more “hillbilly” than the country musicians themselves. Elvis also had no input on the musical material; although he liked the main ballad intended for the film, the other three songs were among the most unremarkable of his 1950s output.

By the time production concluded, “The Reno Brothers” had been retitled “Love Me Tender.” We will revisit Elvis’s film career in a future installment.

The period marked by elvis singing heartbreak hotel and his subsequent RCA recordings solidified his transformation from a promising regional talent to a global phenomenon. The song’s massive success was the catalyst that ignited his unparalleled career, setting the stage for his dominance in music and his eventual pivot to Hollywood, forever cementing his legacy as the King of Rock and Roll.