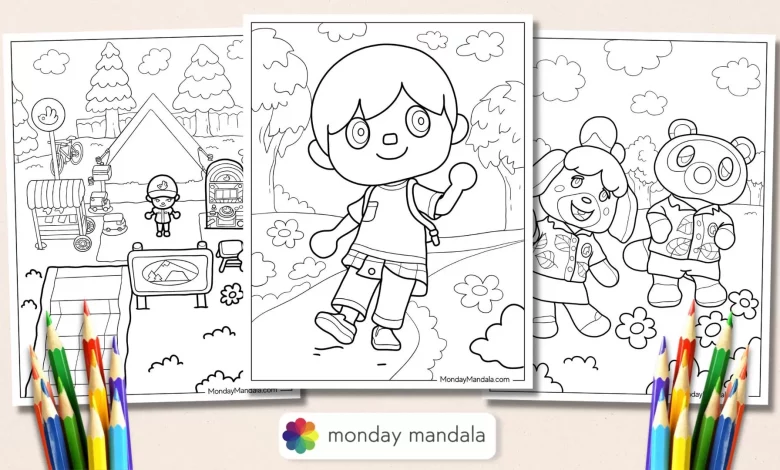

Pack your bags and prepare for a creative journey to your favorite island getaway with our collection of 22 free Animal Crossing New Horizons Coloring Pages! These printable sheets let you dive into the charming and relaxing world of Animal Crossing, the beloved Nintendo video game series known for its quirky animal villagers and endless customization. Bring your favorite moments and characters to life with color!

This series features a variety of delightful illustrations capturing the essence of island life. You’ll find beloved characters ready for your artistic touch, including the cool canine musician K.K. Slider, the diligent and cheerful Isabelle, the entrepreneurial raccoon Tom Nook, and many other familiar faces and scenes drawn from the popular game. These pages offer a fantastic way for fans of all ages to engage with the game’s universe offline.

How to Get Your Free Coloring Pages

Using these free printables is simple. Just click on any of the text links below. Each link will open a high-resolution PDF version of the coloring page in a new browser tab. From there, you have the option to download the file directly to your device or print it out immediately. Let your creativity flow and color your favorite Animal Crossing scenes!

All the PDF coloring pages are designed for standard US letter size paper (8.5 x 11 inches), but they are also formatted to fit perfectly on A4 paper sizes without any scaling issues.

Printable Animal Crossing New Horizons Coloring Pages

Here is the full list of available coloring sheets:

- Villager With Sweeping Net Catching Butterfly

- Simple Isabelle Waving Coloring Page For Preschoolers

- Big Animal Crossing House With Villager, Tom, And Friends Coloring Sheet

- Girl In Animal Crossing New Horizons Coloring Page

- Detailed Animal Crossing Town With Villagers Coloring Page

- Animal Crossing Villager Watering Plants Coloring Sheet

- Animal Crossing Villager Standing In Front Of House Coloring Sheet

- Animal Crossing New Horizons Villagers With Friends On Island

- Animal Crossing Marina Amiibo At The Beach Coloring Sheet

- Animal Crossing Charlise Coloring Sheet

- Outdoor Bonding In Animal Crossing Coloring Page

- Kawaii Tom Nook Coloring Page For Kids

- Isabelle, Tom, Tommy, Timmy, And K.K. Slider Coloring Page

- Isabelle With Tom Nook, Tommy, and Timmy

- Easy Isabelle Coloring Sheet For Kids

- Cute Peppy Outline Coloring Page

- Boy Villager In Animal Crossing Coloring Sheet

- Animal Crossing Villager With Flower Crown

- Animal Crossing Villager In Pocket Camp

- Animal Crossing Villager And Friends Gardening

- Animal Crossing Julian The Unicorn Coloring Page

- Animal Crossing Isabelle And Tom Nook In Summer Outfits

10 Craft Ideas to do With Animal Crossing Coloring Pages

Once you or your little ones have finished coloring these charming Animal Crossing pages, don’t just put them aside! Here are 10 creative craft ideas to give your artwork a new life:

1. Design a Village or Island Scene

Create your own Animal Crossing world on a large poster board. Draw an island or village backdrop. Carefully cut small slits in various places. Cut out the colored characters from the pages, staple them to toothpicks, and slide them into the slits. You can reposition your villagers anytime!

2. Create a Fancy Animal Crossing Fan

This is a simple craft great for younger kids. Cut a finished coloring page into long vertical strips (about 1.5 inches wide). Stack the strips neatly and punch a small hole through the bottom of the stack. Secure them with a paper fastener. When you fan the strips out, the picture reappears on a functional fan.

3. 3D File Cabinet Decorations

Brighten up plain file cabinets or lockers. Carefully cut out colored Animal Crossing characters and items (like fruit, shells, fish). Glue a thin layer of cotton batting or craft foam to the back, then glue this to thin cardboard trimmed to the cutout’s shape. Attach craft magnets to the back and decorate any metal surface.

4. Island Themed Animal Crossing Craft

Capture the island vibe with this craft. Take a paper plate and spray paint it light blue. Use dark blue yarn to create “water” by wrapping it around the bottom half of the plate, securing it with craft glue. Cut out your colored characters and tuck them into the yarn “ocean” for a cute 3D effect.

5. Unique Wall Art with Bells

Cut out a favorite colored character and glue it onto a colorful background (cardstock or construction paper). Glue about five cotton balls in an arch above the character’s head. Cut out Bell shapes (the game’s currency) from another page or draw them freehand. Glue one Bell onto each cotton ball – it looks like the character is juggling Bells!

6. Make Animal Crossing Gyroids

Use empty paper towel rolls as a base. Cover them with construction paper in gyroid colors (orange, pink, yellow). Decorate the tubes with cutouts of characters, Bells, or collectibles from the colored pages. Add pipe cleaner arms and wiggle eyes. Small drink umbrellas make perfect hats for these quirky decorations.

7. Decorate a Classroom Door

Have each child draw the iconic Bell sack from the game and write their name on it. They then cut out their colored Animal Crossing character. Use colorful yarn to attach the character cutout to the sack, making it look like the character is parachuting down. These make a delightful classroom door decoration.

8. Animal Crossing Farmhouse Fun Game

Use a coloring page featuring the farmhouse. Have kids color and cut out various collectibles (shells, fish, fruit). Write a point value on the back of each cutout. Place the items in the windows and doorway of the colored farmhouse picture. Kids can play a game by randomly picking items and adding up points.

9. One-of-a-Kind Hanging Decoration

Color various characters and collectibles. Laminate the cutouts using contact paper or clear tape. Punch a hole at the top of each cutout. String them vertically using colorful embroidery thread, placing craft beads between each cutout for separation. Hang it up as a unique mobile or ornament.

10. Create a Wild World Wreath

Twist brown packing paper into a circle to form a wreath base. Spray paint it green. Color and cut out various characters from the Animal Crossing: Wild World style or any other pages. Glue them randomly around the wreath’s circumference. Apply a coat of clear acrylic spray for protection and add a decorative bow at the top.

Conclusion

Immerse yourself in the delightful world of Animal Crossing New Horizons with these 22 free printable coloring pages. Perfect for fans of all ages, these sheets offer hours of creative fun, allowing you to bring your favorite characters and island scenes to life. Download your chosen designs, grab your coloring tools, and enjoy a relaxing activity. Don’t forget to try the craft ideas to showcase your finished masterpieces in unique ways!