Bob Dylan Willie Nelson: A History of Iconic Collaborations

Tomorrow night marks the kickoff of Willie Nelson’s annual Outlaw Music Festival Tour, and this year, a legendary peer joins him for the entire run: Bob Dylan. The prospect has ignited speculation among fans: will these two titans of American music, Bob Dylan Willie Nelson, share the stage? Their history suggests it’s a strong possibility, built on over five decades of mutual respect and occasional collaboration.

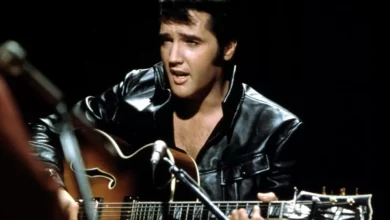

Bob Dylan and Willie Nelson share a moment backstage, iconic musicians headlining the Outlaw Tour.

Dylan himself lauded Nelson in his book, The Philosophy of Modern Song, dedicating separate chapters to Nelson’s work – a unique honor in the volume. He praised Nelson’s interpretative power (“sing the phone book and make you weep”) and his songwriting prowess (“could also write the phone book”). As anticipation builds for the Outlaw tour, let’s delve into the history of their shared performances and studio work.

Early Encounters: 1973 Durango Meeting

The first documented meeting between Bob Dylan and Willie Nelson appears to be in 1973, during the filming of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid in Durango, Mexico. Kris Kristofferson, Dylan’s co-star, recounted introducing them. He’d told Dylan about Nelson’s genius and questioned why he wasn’t more famous. According to Kristofferson:

“So, the next day, Bob calls Willie up and gets him to come down to the set, and he made him play his old Martin guitar for ten hours straight. They ended up doing all these old Django Reinhardt tunes. It was fabulous.”

Joe Nick Patoski’s biography Willie Nelson: An Epic Life confirms Nelson traveled to Durango with friends to watch the filming. Patoski writes that Nelson “ended up serenading the cast and crew all day long at Peckinpah’s house, gladly accommodating Dylan’s requests to hear more and more.” Nelson observed Dylan was “a little shy, scared to death… They had him jumpin’ and runnin’ on them horses, and he ain’t no cowboy.”

Further brief encounters reportedly occurred in Los Angeles shortly after, with Clinton Heylin’s A Life in Stolen Moments noting Dylan attending a Willie Nelson recording session with Leon Russell and Kris Kristofferson in February 1973, and attending a Waylon Jennings show with Nelson sometime in March or April.

Rolling Thunder Revue: 1976 Houston Show

By 1976, Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue tour faced flagging ticket sales on its southern leg. To boost attendance for a Houston show (after another was cancelled), Willie Nelson was brought in as a special guest – his sole appearance on the tour. Musician Kinky Friedman described it as calling in Nelson “as a fireman to bail out Bob.”

Gary Burke, the tour’s percussionist, remembered the logistical scale: “It was like two French foreign legions showing up at this venue… That show easily hit the six-hour mark.” He also recalled Nelson visiting Dylan’s dressing room beforehand, with Dylan asking him to play “that thing about the stranger, the guy with the red hair,” likely referring to “Red Headed Stranger.”

The night culminated in a massive jam session. Burke described the scene: “There had to be 20-some-odd musicians on stage that night… Somebody had a great idea, ‘Why don’t we do ‘Will the Circle Be Unbroken’?’ As soon as they hit the first chord, it was like complete white noise.” Unfortunately, no known recording exists of this first public performance featuring both Bob Dylan and Willie Nelson.

The 1980s: Charity and Golf Chats

“We Are the World” (1985)

Both Dylan and Nelson participated in the star-studded “We Are the World” recording session in 1985. While surrounded by dozens of other artists, a photograph captured a private conversation between the two.

Reporter David Breskin documented the chat in the book We Are the World: The Photos, The Music, and the Inside Story. The surprising topic? Golf. After discussing Nashville’s changes, Nelson asked Dylan if he played. Huey Lewis joined in, extolling the virtues of golf on the road. Nelson explained scramble formats to a seemingly bemused Dylan (“It’s real noncompetitive then?”). The conversation, bizarrely set against Stevie Wonder playing piano nearby and Bob Geldof discussing famine relief with Bruce Springsteen, ended with Dylan and Nelson exchanging numbers and tentatively planning a collaborative album in Hawaii – a project that seemingly never materialized.

Bob Dylan and Willie Nelson featured on the iconic LIFE magazine cover for ‘We Are the World’.

Farm Aid Genesis (1985)

A more impactful 1985 event stemmed from Dylan’s appearance at Live Aid. During his set, Dylan mused aloud, “Wouldn’t it be great if we did something for our own farmers right here in America?” Willie Nelson heard this remark and took action. Two months later, the first Farm Aid concert was held, founded by Nelson. Dylan, backed by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, performed at the inaugural event. Nelson joined Dylan’s band for three songs, a largely symbolic gesture as his guitar wasn’t amplified and he didn’t sing lead, but it underscored their shared commitment.

The 1990s: Bobfest and “Heartland”

Bobfest Tribute (1992)

At the 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration for Bob Dylan (“Bobfest”) at Madison Square Garden in 1992, Willie Nelson was among the performers paying tribute. He delivered a standout version of Dylan’s relatively recent song “What Was It You Wanted” from the 1989 album Oh Mercy. Nelson had already recorded the track for his upcoming album Across the Borderline, and his performance, backed by shared producer Don Was on bass, was noted for its sensitivity.

Co-writing and Recording “Heartland” (1992)

The day following Bobfest, Dylan joined Nelson in the studio to record vocals for “Heartland,” a song they co-wrote. Nelson described the process: producer Don Was brought him a tape of Dylan humming a melody with the word “heartland” recurring. Nelson “took the word and the melody and wrote a song around it.” He added that this fulfilled a long-standing joke about writing an album together. According to reports, the studio duet happened spontaneously because they enjoyed collaborating at Bobfest.

Drummer Jim Keltner, who played on the track, reflected: “Willie Nelson and Bob Dylan are two of the most distinctive voices… to hear them sing together is beautiful. I love how they sound on ‘Heartland’ together. I don’t think they did enough of that.”

TV Performances (1993)

The public first heard Dylan and Nelson perform “Heartland” together during a Nashville TV taping for A Country Music Celebration in January 1993. Dylan sported a cowboy hat and a vibrant jacket for the nasal-inflected duet.

Three months later, they appeared on Willie Nelson’s The Big Six-O birthday special in Austin. Instead of “Heartland,” after Dylan performed Stephen Foster’s “Hard Times,” Nelson joined him for Townes Van Zandt’s “Pancho & Lefty”—a song Dylan would later praise extensively in The Philosophy of Modern Song.

El Rey Theatre Appearance (1997)

During Dylan’s five-night residency at Los Angeles’ El Rey Theatre in 1997, Willie Nelson served as the opening act on the final night. Nelson performed his set backed by members of Dylan’s band (Tony Garnier, Larry Campbell, Bucky Baxter) along with his own harmonica player, Mickey Raphael. While Nelson didn’t join Dylan onstage that night, their paths crossed again within the same venue.

The 2000s: TV Specials and Ballpark Tours

Outlaws and Angels TV Special (2004)

Dylan once again answered Nelson’s call for a television appearance in 2004 for the special Willie Nelson & Friends: Outlaws and Angels. Alongside guests like Merle Haggard and Keith Richards, Dylan joined Nelson for a rendition of Hank Williams’ “You Win Again.” While Nelson sounded strong, Dylan’s voice was notably raspy, and his guitar solo was ill-timed.

Minor League Ballpark Tours (2004, 2005, 2009)

The mid-to-late 2000s saw Bob Dylan Willie Nelson embark on joint tours playing minor league baseball stadiums in the summers of 2004, 2005, and 2009. Their frequency of performing together decreased over these tours.

- 2004: This tour featured the most collaborations. They initially performed “Milk Cow Blues” together once, based on Nelson’s arrangement. They then switched to “I Shall Be Released,” a frequent choice for Dylan guest spots, with Nelson taking verses. Mid-tour, they replaced it with their co-written “Heartland,” marking the only times Dylan performed it live, often joined by Willie’s sons Lukas and Micah.

- 2005: No duets occurred during the standard tour dates. However, at Willie’s annual Fourth of July Picnic in Texas, they reprised their “You Win Again” duet from the TV special. Again, reports suggest Dylan struggled vocally.

- 2009: Bob Dylan and Willie Nelson did not perform together at all during this final ballpark tour iteration.

Looking Ahead: The Outlaw Tour

From serendipitous meetings in Mexico to shared stages at historic benefit concerts and cross-country tours, the collaborative history of Bob Dylan and Willie Nelson is rich and varied. Their mutual admiration has spanned decades, punctuated by memorable, if sometimes imperfect, musical moments. As they embark on the Outlaw Music Festival Tour together, fans eagerly await the next chapter, wondering if and how these two American musical icons will once again share the spotlight.