From Rockabilly King to Pop Icon? Elvis Presley’s Post-Army Evolution

Elvis Presley’s highly anticipated return from the U.S. Army in 1960 marked a crucial turning point in his career. After fundamentally changing the landscape of popular music in the late 1950s with his raw, dynamic Elvis Rockabilly Songs and electrifying stage presence, he stepped back into a vastly different world, both personally and musically. This period saw him navigate the complexities of grief, new relationships, and a rapidly evolving music industry, while facing pressure from his management to carve out a new image. His first recordings and ventures post-discharge would set the stage for the rest of the decade, revealing both his enduring artistic capabilities and the external forces that would shape his output.

Just as I began recording this analysis, the music world lost a titan: Little Richard. While we’ve previously explored his seismic impact through songs like “Tutti Frutti” and “Keep A Knockin’,” his importance to 20th-century music, including the very foundation upon which figures like Elvis built their careers, cannot be overstated. Arguments can be made for the relative importance of Elvis, Chuck Berry, or Little Richard, but their collective influence on rock and roll is undeniable. Without Little Richard’s pioneering spirit and sound, much of the music that followed 1955, and indeed podcasts like this, would not exist. Though few pioneers from that era remain, none held a link as vital in the historical chain as Richard Penniman. His passing is a moment to reflect on the force of nature who rightly called himself the King and Queen of Rock and Roll.

Returning to Elvis, his two-year military service undeniably changed him. He grappled with the death of his mother, experienced separation from his familiar world, and met Priscilla Beaulieu, who would later become his wife. The music scene had shifted dramatically during his absence. The rockabilly explosion had faded from the charts, and many of his contemporaries had transitioned into different styles – Roy Orbison into orchestrated pop, Johnny Cash deeper into country. Only a few, like Gene Vincent, struggled to maintain their chart success in the US.

Yet, Elvis himself had remained a chart presence. RCA strategically released singles from a small stockpile recorded in 1958, including hits like “Wear My Ring Around Your Neck,” “Hard-Headed Woman,” “One Night,” “I Need Your Love Tonight,” and “A Big Hunk O’ Love.” They also repackaged earlier single-only tracks into new albums, successfully keeping Elvis in the public eye without new recordings. This carefully managed presence was part of Colonel Tom Parker’s strategy: record only what was contractually obligated to ensure leverage in future negotiations.

This meant Elvis had little downtime upon returning. After just over two weeks to settle into Graceland – the home he’d barely inhabited before the draft, now shared with his father and his father’s new, much younger girlfriend, whom Elvis reportedly disapproved of – he was back in the studio. The goal was to record material for his first new album in two and a half years, following his Christmas album.

A few weeks prior, we touched upon the Nashville Sound, a new trend in country music significantly shaped by Chet Atkins, who had produced some of Elvis’s early sessions. Many members of the Nashville A-team, the session musicians integral to this sound under producers like Atkins and Owen Bradley, had played on Elvis’s last 1958 session. They were assembled again for the 1960 return sessions, though reportedly told they were playing for Jim Reeves to avoid fan crowds.

With Chet Atkins in the control booth, the lineup included Hank “Sugarfoot” Garland on guitar (a brief replacement for Scotty Moore on stage previously), Floyd Cramer on piano (a constant since Elvis’s first RCA session), Buddy Harman (who had doubled DJ Fontana) and another drummer, and Bob Moore on bass. The Jordanaires, who had sung on Elvis’s pre-Army records and were part of the Nashville A-Team, provided backing vocals. Scotty Moore and DJ Fontana were present but in diminished capacities – Scotty on rhythm guitar only, DJ as one of two drummers. Notably, Bill Black, who often sought more recognition and was now successful with his Bill Black Combo, was not included and never recorded with Elvis again. While Elvis had defined the energy of early Elvis Rockabilly Songs with this original trio, his post-Army sessions marked a significant sonic departure, embracing the polished “Nashville Sound” instrumentation.

The first session started slowly, featuring ordering food, listening to demos, and even Elvis and Bobby Moore practicing karate moves. The initial song attempted, Otis Blackwell’s “Make Me Know It,” required nineteen takes to get right. Despite the initial hesitation observed by those in the studio, Elvis’s voice had improved dramatically during his service; he had practiced extensively, reportedly adding a full octave to his range, and was eager to tackle diverse material. The strongest track from this early session was Pomus and Shuman’s “A Mess of Blues.”

However, the song chosen for the first single was “Stuck on You,” written by Aaron Schroeder and Leslie McFarland, considered by some a more mediocre track. Demand was so high that the single, backed with “Fame and Fortune,” was released within seventy-two hours. RCA had printed 1.4 million copies based on advance orders, with sleeves simply announcing “Elvis’ 1st New Recording For His 50,000,000 Fans All Over The World” because the specific songs were unknown when sleeves were printed.

By the time “Stuck on You” was released, Elvis had already made his only television appearance for the next eight years. Colonel Parker had arranged The Frank Sinatra Timex Show: Welcome Home Elvis. Although Sinatra had previously been critical of Elvis, money and opportunity prevailed. The show featured standard Rat Pack humor with Joey Bishop and Sammy Davis Jr. Scotty Moore recalled the train journey to Florida for the taping as an event akin to presidential funeral processions, with crowds lining the tracks. He also remembered Elvis offering him “little pills” he had taken in the Army. While friendly on the train, the Colonel reportedly forbade Scotty, DJ, and the Jordanaires from socializing with Elvis during rehearsals in Miami.

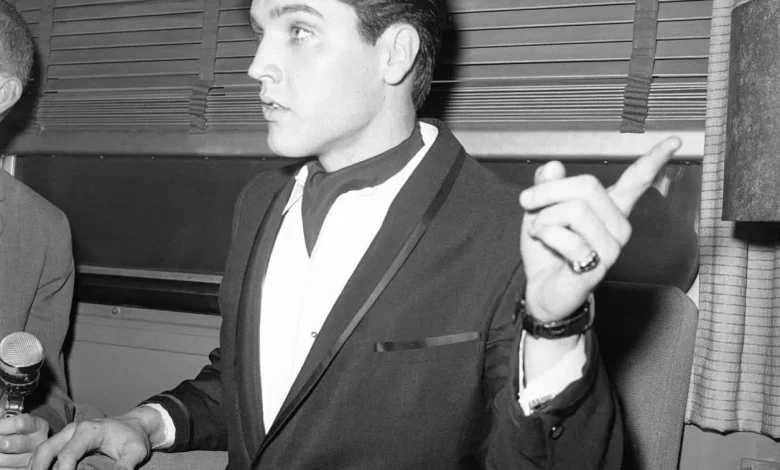

The TV special was a rare live performance for Elvis in the sixties. Dressed formally, seemingly aiming for a family-friendly image, he appeared initially uncomfortable crooning “Fame and Fortune.” He found his footing on “Stuck on You” before joining Sinatra for a duet where Sinatra sang “Love Me Tender” and Elvis sang Sinatra’s “Witchcraft.” Footage reveals Elvis becoming comfortable, arguably outshining Sinatra, who appeared somewhat mocking of “Love Me Tender,” while Elvis played Sinatra’s song straight but with a knowing self-awareness.

A week later, Elvis returned to the studio for the rest of the tracks for his album Elvis is Back! With the same musicians plus Boots Randolph on saxophone, this session yielded some of his most impressive post-rockabilly material. They produced a version of “Fever” comparable to Peggy Lee’s famous rendition, with minimal backing. “Like a Baby,” a Jesse Stone composition, showcased Elvis’s blues vocals.

A significant departure was the adaptation of Tony Martin’s 1950 hit “There’s No Tomorrow,” based on “O Sole Mio.” Having rehearsed it in Germany, Elvis wanted to record it. Freddy Bienstock of Hill and Range commissioned new English lyrics, creating “It’s Now or Never.” Elvis delivered several near-perfect takes but struggled with the powerful final note. Engineer Bill Porter suggested splicing, but Elvis was determined to perform it in one take. His successful attempt resulted in an extraordinary performance, unlike anything heard in his earlier, iconic elvis rockabilly songs. This track, along with another non-album single from the session, “Are You Lonesome Tonight?”, would top the charts.

“Are You Lonesome Tonight?” was a 1926 song, a hit for Al Jolson among others. Colonel Parker reportedly wanted Elvis to record it for two reasons: his sentimental association with Gene Austin, an artist he had promoted, and because it was his wife Marie’s favorite song. For this recording, Elvis requested only a few musicians (acoustic guitar, bass, drums) and that the lights be turned off. He did one take, then a false start before wanting to give up. RCA’s Steve Sholes insisted it could be a hit. Despite completing it, the released take contains a mistake: someone bumping a mic during the spoken bridge due to the darkness. Despite the flaw, it became a massive hit and a staple of his live shows.

During this single overnight session, Elvis and the band recorded twelve songs spanning an almost inconceivable stylistic range: a Leiber and Stoller rocker, a cover of Clyde McPhatter’s “Such a Night,” the blues standard “Reconsider Baby,” the Latin-flavored pop of “The Girl of My Best Friend,” and even a Louvin Brothers-style duet with Charlie Hodge. In essence, Elvis masterfully covered nearly every significant American popular song style of 1960. Between the two sessions, he recorded eighteen tracks – three singles and a twelve-track album. Though smoother than his raw Sun Records period, these recordings are arguably as artistically successful and represent his best creative work since signing with RCA. All three singles hit number one, and Elvis Is Back! peaked at number two, selling half a million copies.

However, just three weeks after this acclaimed session, Elvis entered a different studio to cut vastly different material. His first post-Army film, “G.I. Blues,” was conceived as a light comedy to establish a new, wholesome image. Elvis reportedly disliked the script and was frustrated to find himself recording songs mainly by journeyman songwriters like Sid Wayne, Abner Silver, Sid Tepper, and Fred Wise, who lacked a feel for rock and roll. Songs like “Wooden Heart,” based on a German folk tune, exemplify this shift.

Criticizing Elvis’s film songs requires context; they were written for specific movie scenes, not necessarily standalone hits. Judging them outside the film is like evaluating a character’s lines as poetry. Yet, Elvis visibly struggled to connect with these performances, unlike the effortless delivery of his earlier work or even the inspired vocals on Elvis is Back! Bones Howe, involved in the sessions, felt Elvis had lost something, now having to try to find his way into performances that once came naturally. The issue wasn’t the Army, but Elvis’s lack of passion for the material.

Elvis reportedly told Colonel Parker that half the film’s songs needed scrapping, but the Colonel insisted he was contractually bound. Elvis gave his best performance despite his lack of enthusiasm. He was placated by promises that his next films would be “proper films” like “Jailhouse Rock” or “King Creole.” The subsequent films, “Flaming Star” (a Western addressing racism, a role originally intended for Marlon Brando) and “Wild in the Country” (a drama about a troubled young writer), featured minimal songs and aimed for serious acting roles.

After filming these three movies, Elvis returned to the studio for another overnight session, resulting in His Hand in Mine, his first full-length gospel album. This record arguably represented the purest expression of his musical desires, fulfilling a long-held dream of singing in a gospel quartet alongside the Jordanaires.

By the end of 1960, Elvis had released two artistically significant albums and three films, two of which he could reasonably be proud of. Yet, the film he disliked, “G.I. Blues,” was the massive success, with its soundtrack topping the charts for eleven weeks and selling a million copies, vastly outselling Elvis Is Back! His Hand in Mine reached number thirteen. This pattern repeated: studio albums were eclipsed commercially by soundtracks like the one for “Blue Hawaii,” a formulaic film packed with frivolous songs.

From this point, Elvis’s career trajectory was set. Colonel Parker steered him away from dramatic roles into three interchangeable, light comedies per year, typically set in exotic locales with minimal plots but filled with forgettable songs. While he occasionally made non-soundtrack recordings that rivaled his best work, the film treadmill dominated his time until 1968. Consequently, Elvis largely became musically irrelevant throughout the decade to the new generation of artists, many echoing John Lennon’s sentiment that “Elvis died when he went into the Army.” We pick up his story again when he finally broke free from this cycle.