Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley, and the Story Behind “I Walk The Line”

Episode thirty-seven of the series “A History of Rock Music” looks at “I Walk The Line” by Johnny Cash, serving as part two of a trilogy exploring the aftermath of Elvis Presley’s departure from Sun Records and the subsequent birth of rockabilly. To fully appreciate this story, consider the interconnected histories of artists like Johnny Cash and Carl Perkins, whose narratives intertwine significantly.

At the close of 1955, the lines between rock and roll, rhythm and blues, and country music were fluid, demonstrating how the history of one popular music genre often encompasses them all. Johnny Cash, an artist widely regarded as the epitome of country music, began his recording career with Sam Phillips at Sun Studios. His early music was stylistically aligned with other rockabilly artists there, and his path would remain intertwined with theirs for decades. The journey of Johnny Cash Elvis Presley Walk The Line is a key part of this narrative, highlighting the pivotal period at Sun.

Cash’s birth name was J.R. Cash, initials given due to his parents’ disagreement over a full name. He used this until joining the Air Force, where regulations required a full name, leading him to adopt John R. Cash. He became Johnny Cash only after becoming a professional musician, retaining the single middle initial. While in the military in Germany, he gained the unique distinction of being the first American to learn of Stalin’s death, having intercepted and decoded the Russian transmissions. However, his true ambition was a career in singing, despite not knowing how to achieve it.

Returning to the US at twenty-two, married, Cash moved to Memphis. Through his brother, he met Luther Perkins and Marshall Grant, colleagues who also played guitar. Initially, the three, sometimes joined by steel player Red Kernodle, were highly unskilled. Yet, they possessed key advantages: a willingness to experiment and Cash’s remarkable voice. Even in his youth, Cash’s voice was impactful – a resonant bass-baritone demanding attention, embodying a gravitas likened to being carved from rock and imbued with the spirit of an Old Testament prophet. While not possessing a wide range, his voice had astonishing sonority.

Cash harbored a strong determination to become a famous singer. Their early sessions focused primarily on gospel songs, reflecting Cash’s deep connection to white Southern Gospel music. A profound religious experience as a child, linked to his elder brother’s deathbed vision of heaven and hell, fueled Cash’s desire to be a gospel singer in tribute to his brother and his love for music.

A turning point occurred during a jam session when Cash introduced his self-written song “Belshazzar,” based on a biblical story. This surprised Perkins and Grant, who hadn’t considered that songs were written. Initially, they all played acoustic guitars, mimicking songs heard on the radio, particularly aspiring to sound like the Louvin Brothers. While enjoyable, these sessions were merely for fun. Cash, however, sought more. This ambition solidified upon hearing Elvis Presley’s “That’s All Right Mama,” a record released the day after Cash returned to the US.

He was drawn to the sound and, crucially, to the DJ mentioning it was on Sun Records, a Memphis-based label. Johnny, Luther, and Marshall went to see elvis presley walk the line perform on a flatbed truck, playing only their single’s two songs. Cash felt a pang of worry – Elvis was a teenager; at twenty-two, had he missed his chance? He spoke briefly with Elvis and attended a proper nightclub set the following night, where he talked to Scotty Moore, seeking advice on getting signed to Sun.

Moore directed him to Sam Phillips. Cash acquired Sun’s phone number and repeatedly called, attempting to reach Phillips, who was frequently traveling to promote the label. Cash understood he needed more than jam sessions; his group needed to evolve into something akin to Elvis, Scotty, and Bill. With Cash as the lead singer and acoustic rhythm guitarist, Luther Perkins acquired an electric guitar, playing simple octave-transposed boogie-woogie basslines. Marshall Grant took up the double bass, taping markers for notes as he was new to the instrument. His playing was necessarily slow and sparse: “Boom [pause] boom [pause] boom [pause] boom.”

Their limitations as musicians inadvertently fostered a unique sound. They compensated by finding ways to make songs work without complex parts. As Luther Perkins later noted, while “hot-shot guitarists race their fingers all over the strings… they’re looking for the right sound. I found it.” Still uncertain about his group’s quality, Cash visited Sam Phillips in person alone.

Phillips was immediately impressed by Cash’s presence – taller and more dignified than typical auditionees, possessing gravitas and star potential. The next day, Cash brought his bandmates. Phillips reassured them that technical skill wasn’t paramount, only the right sound. After rehearsing, they returned to audition. Their steel player, Red Kernodle, became too nervous to tune his guitar and left, feeling he was hindering them. The audition continued with the remaining trio, who would become known as the Tennessee Three, later renamed Johnny Cash and the Tennessee Two.

Phillips liked their sound but wasn’t interested in gospel music, having found no commercial success with it. While Cash denied the urban legend that Phillips told him to “go home and sin, then come back with a song I can sell,” it’s true Phillips sought more commercial material. Taking the hint, Cash wrote secular songs. The first, “Hey Porter,” inspired by trains, featured the “boom-chick-a-boom” rhythm that became his signature.

Phillips approved, and they recorded “Hey Porter.” Lacking a drummer, Cash deadened his acoustic guitar strings with paper to simulate a snare drum, creating the iconic boom-chick sound – a country take on the two-beat rhythm, born from their instrumental limitations, yet highly effective.

For the B-side, Cash presented “Folsom Prison Blues.” Its originality was loose, inspired initially by the film “Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison” seen in Germany. Two musical inspirations cemented the idea: Gordon Jenkins’ “Crescent City Blues,” which Cash heard on an album, and Little Brother Montgomery’s earlier song of the same name. The third crucial influence was Jimmie Rodgers’ “Blue Yodel #1” (“T For Texas”). The line “I’m gonna shoot poor Thelma, just to see her jump and fall” deeply affected Cash, embodying the most morally bankrupt person imaginable. He combined this bleak amorality with the Folsom idea, altering “Crescent City Blues” lyrics just enough.

Phillips deemed “Folsom Prison Blues” unsuitable as the B-side, opting instead for the sadder “Cry Cry Cry.” However, “Folsom Prison Blues” was saved for later. The Sun contract was solely with Cash; Phillips didn’t want obligations to the sidemen, though money was split roughly equitably. “Hey Porter” and “Cry Cry Cry” both charted. “Folsom Prison Blues” became Cash’s second single, defining his career, reaching number four on the country chart, and establishing him as a country star.

Around this time, Sun signed Carl Perkins, creating tension. Cash felt sidelined compared to Perkins, believing Phillips lost interest in promoting his records. This pattern – Phillips focusing intensely on new discoveries, making established artists feel neglected – ultimately contributed to Sun’s later struggles as artists moved to major labels. Phillips maintained he had to build new careers and that established artists forgot his past help when he did the same for others.

Despite this, Cash and Carl Perkins became close friends. Cash was even closer to Carl’s brother, Clayton, whose humor appealed to him. Cash and Perkins co-wrote “All Mama’s Children,” the B-side to Perkins’ “Boppin’ the Blues.” While not their best song, it began a lasting working relationship benefiting both.

Cash built a following, mirroring Elvis’s path. He was managed by Elvis’s first manager, Bob Neal, and gained a regular spot on the Louisiana Hayride radio show, where Elvis built his reputation. This positioned Cash as a rock and roll star alongside Carl Perkins, which broadened his audience. Many mid-fifties fans who wouldn’t listen to “country” embraced Cash, keeping him appealing to rock audiences. His promotion as a rock and roller in 1955-56 directly links to his successful American Recordings comeback decades later.

However, a conflict arose when Cash brought a new song to Phillips about his struggle on the road to remain faithful to his wife and implicitly, his faith. This song was likely inspired by Merle Travis’s hit “Sixteen Tons,” which Cash admired. The image of “elvis in walk the line” or simply “walking the line” from that song stuck with Cash, becoming the central metaphor for his song written on the road about fidelity.

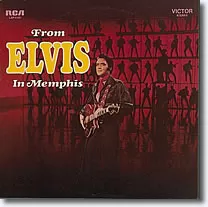

“I Walk The Line” sparked significant debate between Cash and Phillips. Cash believed it was a great song, possibly his best, intending it as a slow, plaintive ballad. Phillips was less impressed with the song itself but saw potential if sped up to match Cash’s rock and roll hits like “Hey Porter.” He wanted a strong rhythm for universality, suitable for Cash’s rock and roll audience. Cash argued against speeding it up, noting his other song, “Get Rhythm,” explicitly mentioned rhythm (“Get rhythm if you get the blues”) and was an uptempo rock and roll track he’d originally considered giving to Elvis.

They compromised, recording both a faster version favored by Phillips and a slower one preferred by Cash. Cash left convinced Phillips would release the slower take, only to be devastated when Phillips released the faster one. Cash recounted calling Phillips upon first hearing it on the radio, saying, “I hate that sound. Please don’t release any more records. I hate that sound.”

Yet, the record became a massive hit, persuading Cash the sound wasn’t so bad. It hit number one on the country jukebox chart, reached the pop Top 20, and sold over two million copies as a single. Commercially, Phillips’ instincts were validated.

“I Walk The Line” possesses a highly unusual structure: a key change after every verse. Normal pop songs usually stay in one key, change keys between sections, or have one key change near the end. “I Walk The Line” moves F -> B♭ -> E♭ -> B♭ -> F (the final F an octave lower). This unique musical arc of rising and falling keys, returning to the original tonal center, mirrors the lyrical metaphors of balance – tides, heartbeats, day and night, dark and light – suggesting the protagonist is precariously “walking a thin line,” liable to fall, reflecting the song’s oscillation and return. What might sound simple is structurally inventive.

The chord sequences within verses are also atypical. Each verse uses only three chords (tonic, subdominant, dominant) but starts with the dominant chord – an unusual, unstable choice reportedly inspired by Cash’s fascination with the sound of a backwards tape. The dominant typically resolves to the tonic at the end of a progression, not starts it. The backwards tape story is also one origin for the humming that precedes each verse, though Cash also claimed it helped him find the starting note amidst the frequent key changes.

This song deviates significantly from typical country or western structures, making it an extraordinarily personal and idiosyncratic record. Despite Sam Phillips’ commercial alterations, it retains Cash’s unique aesthetic. It stands as a strong contender for Sun Records’ best output, a high bar given their roster. Its two-million-copy success in a market often stereotyped as conservative challenged those assumptions.

“I Walk The Line” was a masterpiece solidifying Johnny Cash’s path toward a long and artistically successful career. However, this career wouldn’t remain at Sun. His life was in turmoil, the marriage so movingly depicted in the song was failing, and he felt a move to a major label, following elvis only the lonely‘s example, would be beneficial. Soon, he would sign with Columbia Records, where he spent most of his career and achieved superstardom. Though we’ll have one last look at his time at Sun in a future episode before discussing his transition and elvis presley heartbreak hotel, the tale of Johnny Cash Elvis Presley Walk The Line captures a critical moment at the crossroads of country, rockabilly, and music history.