Elvis in Vegas: Suspicious Minds and the Landmark 1969 Engagement

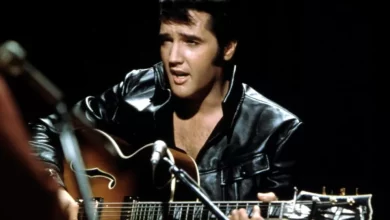

Following his successful December 1968 NBC TV special, the ’68 Comeback Special, Elvis Presley entered the recording studio in January 1969 determined to capitalize on his revitalized career momentum. This period saw The King of Rock & Roll return to Memphis, Tennessee, for fruitful sessions at American Sound Studio. Among the significant tracks laid down was “Suspicious Minds“, a song that would become his seventh and final number one single on the Billboard Hot 100 on November 1, 1969. While many of his earlier hits predated the Hot 100’s 1958 launch, “Suspicious Minds” cemented his return to chart dominance after years focused primarily on movie soundtracks. Presley himself expressed excitement about recording back in Memphis for the first time since 1955, calling the non-film-tied sessions “especially refreshing.” This era marked a significant rejuvenation for Presley’s pop music career, culminating in “Suspicious Minds” becoming his first Hot 100 chart-topper since 1962’s “Good Luck Charm.”

The Recording of Suspicious Minds

Recorded on January 23, 1969, during the American Sound sessions, “Suspicious Minds” was penned by Mark James. These sessions in Memphis, guided by producer Chips Moman at the small American Sound Studios, are widely regarded as producing some of the finest music of Presley’s career, often compared favorably to his innovative early work at Sun Records.

Inspired by the success of his television special, Elvis poured his heart and soul into making quality music that would yield hit records. The atmosphere in Memphis provided a stark contrast to the perceived staleness of RCA’s Nashville studios at the time. Working with top-notch Memphis musicians, the resulting sound was fresh and gutsy, capturing his creative excitement and energy after years of what he likely viewed as movie boredom.

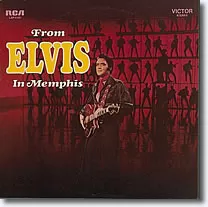

The extensive recording work at American Sound Studio yielded two important albums: From Elvis In Memphis and Back In Memphis. These sessions also produced four hit singles released between late 1969 and 1970: “In the Ghetto,” “Suspicious Minds,” “Don’t Cry, Daddy,” and “Kentucky Rain.”

Suspicious Minds Lyrics

Words & Music by Mark James

We’re caught in a trap

I can’t walk out

Because I love you too much baby

Why can’t you see

What you’re doing to me

When you don’t believe a word I say?

We can’t go on together

With suspicious minds

And we can’t build our dreams

On suspicious minds

So, if an old friend I know

Drops by to say hello

Would I still see suspicion in your eyes?

Here we go again

Asking where I’ve been

You can’t see these tears are real I’m crying

We can’t go on together

With suspicious minds

And we can’t build our dreams

On suspicious minds

Oh let our love survive

Or dry the tears from your eyes

Let’s don’t let a good thing die

When honey, you know I’ve never lied to you

Mmm yeah, yeah

Recorded: 1969/01/23, first released on single

The Landmark 1969 Las Vegas Engagement

Building on the momentum from his recording success and the ’68 Special, Elvis Presley made a pivotal move that would redefine his live performance career: a residency in Las Vegas. Starting on July 31, 1969, Elvis was booked for a four-week, fifty-seven show engagement at the newly constructed International Hotel, which boasted the largest showroom in the city.

For these performances, Elvis assembled a top-tier band featuring rock and roll musicians, an orchestra, a male gospel backing group, and a female soul/gospel backing group. After several weeks of rehearsals, the show opened to immediate acclaim. The performances offered a dynamic blend of fresh arrangements of classic Elvis hits, exciting new material from the Memphis sessions (including songs like “elvis suspicious minds las vegas“), covers of contemporary and past hits by other artists, alongside charming on-stage antics and personal reflections.

This engagement shattered existing Las Vegas attendance records and garnered rave reviews from both the public and critics, confirming the completeness of his comeback. The live album, Elvis in Person at the International Hotel, Las Vegas, Nevada, was recorded during this residency and quickly released, capturing the excitement of these shows. Physically fit and lean, Elvis wore simple, unique, karate-inspired two-piece outfits designed by Bill Belew, who had also created his wardrobe for the ’68 special. These were the precursors to his iconic one-piece jumpsuits that would evolve over the following years.

1969 Recording Sessions & Activities

The year 1969 was incredibly busy for Elvis, marking his return to prolific recording and live performance.

American Sound Studio Sessions (Memphis, Tennessee) – January/February 1969:

- January 13: “Long Black Limousine,” “This Is The Story”

- January 14: “Come Out Come Out” (Wherever You Are) (Fast – Track), “Memory Revival” (Slow – Track), “Wearin’ That Loved On Look,” “You’ll Think Of Me,” “A Little Bit Of Green”

- January 15: “Gentle On My Mind,” “I’m Movin’ On,” “Don’t Cry Daddy” (Track), “Poor Man’s Gold” (Track)

- January 16: “Inherit The Wind” (Track), “Mama Liked The Roses” (Track), “My Little Friend” (Track)

- January 20: “Gentle On My Mind” (Vocal Replacement), “Gentle On My Mind” (Harmony Vocal Overdub), “Rubberneckin’”

- January 21: “In The Ghetto,” “My Little Friend” (Vocal Overdub), “Inherit The Wind” (Vocal Overdub), “Mama Liked The Roses” (Vocal Overdub), “Mama Liked The Roses” (Harmony – Vocal Overdub), “I’m Movin’ On” (Vocal Replacement), “Long Black Limousine” (Vocal Repair), “Don’t Cry Daddy” (Vocal Overdub), “Don’t Cry Daddy” (Harmony – Vocal Overdub), “Poor Man’s Gold” (Vocal Overdub), “Wearin’ That Loved On Look” (Vocal Repair), “You’ll Think Of Me” (Vocal Replacement), “This Is The Story” (Vocal Replacement), “From A Jack To A King”

- January 22: “Hey Jude,” “In The Ghetto” (Vocal Replacement)

- January 23: “Without Love,” “I’ll Hold You In My Heart,” “I’ll Be There,” “Suspicious Minds,” “Suspicious Minds” (Harmony – Vocal Overdub)

- February 17: “Stranger In My Own Home Town,” “True Love Travels On A Gravel Road,” “This Time / I Can’t Stop Loving You” (Informal Jam), “True Love Travels On A Gravel Road”

- February 18: “And The Grass Won’t Pay No Mind,” “Power Of My Love,” “After Loving You”

- February 19: “Do You Know Who I Am?”, “Do You Know Who I Am?” (Vocal Repair), “Kentucky Rain,” “Kentucky Rain” (Remake)

- February 20: “Only The Strong Survive,” “It Keeps Right On A-Hurtin’”

- February 21: “Any Day Now,” “If I’m A Fool (For Loving You),” “The Fair Is Moving On,” “Memory Revival” (Fast – Track)

- February 22: “Any Day Now” (Vocal Repair), “True Love Travels On A Gravel Road” (Harmony – V.O.), “Power Of My Love” (Harmony – Vocal Overdub), “Do You Know Who I Am?” (Harmony – Vocal Overdub), “Who Am I?”

Hollywood Soundtrack Recording (Decca Universal Studio) – March 1969:

- March 5: “Let Us Pray” (Track), “Change Of Habit,” “Let’s Be Friends,” “Let’s Be Friends” (Work Part – Ending), “Let’s Be Friends” (Composite), “Have A Happy” (Track)

- March 6: “Let Us Pray” (Vocal Overdub), “Have A Happy” (Vocal Overdub)

Nashville Sessions (RCA Studio A) – September 1969:

- September 26: “Let Us Pray” (Vocal Replacement), “A Little Bit Of Green” (Vocal Replacement), “A Little Bit Of Green” (Harmony – Vocal Overdub), “And The Grass Won’t Pay No Mind” (Vocal Replacement)

Other activities in 1969 included the release of the movie “Charro!” in March, which did not perform well at the box office, and recording work related to his final acting role in “Change of Habit.”

The Aloha From Hawaii Special (1973)

Though occurring later, the original source includes details about the historic Elvis: Aloha from Hawaii – Via Satellite special. Performed at the Honolulu International Center Arena on January 14, 1973, and broadcast live via satellite, this show was beamed to numerous countries worldwide, including Australia, South Korea, Japan, Thailand, the Philippines, and South Vietnam, with a delayed broadcast in Europe and America. The January live broadcast attracted massive viewing audiences internationally (e.g., 91.8% in the Philippines, 70% in Hong Kong), while the delayed NBC airing in April captured 51% of the American television audience, seen by more US households than the moon landing.

Seen by an estimated one to 1.5 billion people in about forty countries, it was an unprecedented global event for a single performer. Elvis commissioned an American Eagle design for his jumpsuit for this show, symbolizing a patriotic message to his vast audience. Physically and vocally, Elvis was in peak form, making it a pinnacle moment of his superstardom. This was the very first satellite show by any entertainer, a challenging feat due to strict timing requirements. Colonel Parker negotiated the deal with NBC, who owned the satellite time. Despite initial nervousness, Elvis became comfortable during rehearsals and delivered a perfect performance. The show was a charity benefit, raising $75,000 for the Kui Lee Cancer Fund in Hawaii through ticket sales (where attendees paid what they could) and concert merchandise.

Songs performed during the Aloha Special included: Also Sprach Zarathrusta – See See Rider – Burning Love – Something – You Gave Me A Mountain – Steamroller Blues – My Way – Love Me – Johnny B. Goode – It’s Over – Blue Suede Shoes – I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry – I Can’t Stop Loving You – Hound Dog – What Now My Love – Fever – Welcome To My World – elvis suspicious minds vegas – Introductions by Elvis – I’ll Remember You – Long Tall Sally / Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On – An American Trilogy – A Big Hunk O’ Love – Can’t Help Falling In Love.

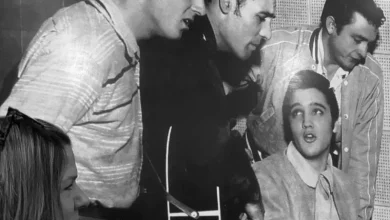

Also mentioned is a “Tupelo’s Own Elvis Presley DVD” featuring previously unreleased 1950s concert film with sound, including songs like “Heartbreak Hotel,” “Don’t Be Cruel,” and “Long Tall Sally,” described as an excellent release for any fan, capturing Elvis in his prime.

Conclusion

The period surrounding 1969 marked a definitive turning point in Elvis Presley’s career. The recording of “Suspicious Minds” in Memphis signaled a return to critical and commercial success after the ’68 Comeback Special. This creative resurgence was amplified by his groundbreaking 1969 engagement at the International Hotel in Las Vegas. These live performances, documented on the elvis suspicious minds las vegas 1970 album, re-established Elvis as a formidable live performer capable of captivating global audiences. From the studio to the stage, 1969 was a year where Elvis proved he was still the King, setting the stage for his continued dominance in the 1970s, highlighted by historic events like the Aloha from Hawaii special. His connection to Las Vegas, often featuring powerful renditions of hits like “elvis presley suspicious minds live in las vegas“, remains a cornerstone of his legacy.