The Genesis of a Legend: Revisiting Elvis Presley’s “That’s All Right, Mama” and Its Live Spark

In the annals of music history, few moments are as pivotal and unexpected as the recording and subsequent impact of Elvis Presley’s first single, “That’s All Right, Mama.” Released on Sun Records in 1954, this seemingly simple track wasn’t just a song; it was the sonic spark that ignited a cultural revolution, merging disparate musical styles and laying the foundation for rock and roll. For Shock Naue Entertainment News, understanding the origins of such iconic moments is key to appreciating the vast landscape of music and its evolution. This dive into the story behind elvis presley that’s alright mama live and its studio birth reveals a confluence of vision, raw talent, and sheer serendipity.

The story begins not with Elvis, but with Sam Phillips, the visionary founder of Sun Records in Memphis. Phillips wasn’t just running a business; he was on a mission he believed could transcend the pervasive racial divisions of the era. His conviction was that if white audiences could only hear and love the music created by Black artists as much as he did, it could help dismantle the color barrier. Having had success but also frustrating experiences leasing recordings by artists like Howlin’ Wolf and Joe Hill Louis to bigger labels (Chess, Duke), Phillips realized he needed his own label to fully control the music and pursue his goal.

Sun Records’ early days saw releases like “Bear Cat,” Rufus Thomas’s answer record to Big Mama Thornton’s hit “Hound Dog.” “Bear Cat” became a surprise R&B hit, reaching number three, but also led to a costly copyright infringement lawsuit. Despite early successes with blues artists, Phillips still hadn’t found the artist who could truly cross over and bring the raw energy and feeling of Black music to a wider white audience, thus fulfilling his grand social and musical ambition.

Phillips was searching for someone who possessed a similar depth of feeling and outsider perspective as the Black blues and R&B artists he admired. This is where Elvis Aaron Presley entered the picture. An introverted, shy young man from a poor sharecropper family in Mississippi, Elvis moved to Memphis and worked as a truck driver. His initial visit to Memphis Recording Service (Phillips’ studio) was to record a two-sided acetate disc – ostensibly a gift for his mother, but also a way to get noticed. He recorded covers of “My Happiness” and “That’s When Your Heartaches Begin.”

Marion Keisker, Phillips’ assistant, heard something unique in the young man – the possibility that he might be the “white man who could sing like a black man” Phillips had been looking for. While Elvis’s performance on those initial ballads didn’t overtly feature a strong blues or R&B vocal style (he sounded more like a smooth crooner in the style of the Ink Spots), both Keisker and Phillips recognized an attitude, an intangible quality that set him apart.

Elvis’s background was crucial to this unique quality. He was an outsider who didn’t comfortably fit into any single social or musical group. Bullied at school, deeply attached to his mother, and terribly shy, he absorbed music from every available source: country groups his mother listened to (like the Louvin Brothers), gospel quartets (especially white “Southern Gospel” groups like the Blackwood Brothers, his favorite), the fiery services at his Pentecostal church, and the blues and R&B he heard on Beale Street, where he also notably bought his clothes, diverging from typical white teenagers. His ideal musical outlet was actually singing harmony in a gospel quartet, not being a solo star. But this broad, unsegmented musical diet meant he effortlessly absorbed and could replicate styles from anywhere. He didn’t own many records but had an incredible ability to hear a song once on the radio, be it by Arthur Crudup or the Ink Spots, and sing it back with remarkable accuracy. He was a sponge, soaking up America’s diverse musical landscape. This ability to synthesize rather than specialize would be key to his sound. If you want to see a comprehensive collection, you can show me a list of elvis presley songs.

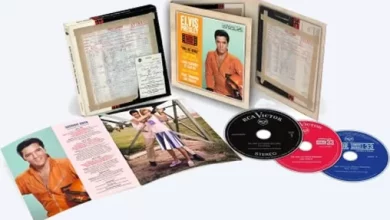

Phillips decided to pair Elvis with two musicians he trusted from the local scene: guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black, members of the country band the Starlite Wranglers. Moore and Black weren’t technical virtuosos, but they played with feeling and instinct – qualities Phillips valued. Their initial rehearsals with Elvis were reportedly awkward, with Elvis still shy and unsure. Moore wasn’t initially impressed, but like Keisker and Phillips, sensed “something” there that warranted further exploration. A list of elvis songs in alphabetical order reveals the breadth of his later catalog, but it all started with this session.

Phillips arranged a recording session at Sun Studio. They tried recording ballads, the style Elvis had presented earlier, but nothing clicked. They experimented with various songs without success until, almost casually during a break, Elvis began messing around with an upbeat version of “That’s All Right, Mama,” a song originally recorded by bluesman Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup in 1946.

Arthur Crudup was a figure steeped in the country-blues tradition, known for improvising and reusing floating lyrics and melodies across different songs. “That’s All Right, Mama” itself evolved from lines Crudup used in earlier tracks like “If I Get Lucky” and his “Mean Old Frisco Blues,” all drawing inspiration from foundational blues artists like Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “Black Snake Moan.” Crudup’s versions were raw, steady, and deeply bluesy, often featuring just his guitar and vocals, maybe with minimal accompaniment. Sadly, Crudup sold the rights to many of his songs early on and saw little to none of the substantial royalties generated by subsequent covers, including Elvis’s massive hit.

When Elvis, Scotty, and Bill started playing “That’s All Right, Mama” in the studio, it was different. It wasn’t a direct imitation of Crudup. They sped up the tempo, infused it with a country “hillbilly” sensibility, replaced drums with Bill Black’s lively, clicking slapback bass, and added Scotty Moore’s clean, rudimentary but effective electric guitar fills. The recording itself, as captured by Sam Phillips, was drenched in a distinctive echo. While it didn’t sound exactly like the Black blues or R&B records Phillips was making, it certainly didn’t sound like typical country music either. It was something new – a blend, a hybrid that would soon be labeled “rockabilly.”

What truly stood out in Elvis’s vocal performance on “That’s All Right, Mama” was an unexpected playfulness and irreverence. Unlike the earnestness of much country music or the grit of the blues origin, Elvis treated the song lightly, almost as a joke, jumping between registers with surprising assurance for a novice performer. This carefree attitude, combined with the energetic, sparse instrumentation and Phillips’ production, gave the track a unique, fresh feel. This early recording offers a glimpse into the raw energy that would later define elvis presley thats alright mama in performances.

For the B-side, they chose another song from a completely different genre: Bill Monroe’s bluegrass standard “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” Again, they didn’t cover it faithfully. They transformed Monroe’s melancholic waltz into an uptempo, driving track with the same slapback bass and echoing vocals as the A-side. This pairing of a blues song on the A-side and a bluegrass song on the B-side, both radically reworked with this new, energetic sound, perfectly encapsulated the fusion that was about to explode. The resulting style on “Blue Moon of Kentucky” is often cited as a foundational example of rockabilly.

A key element in the unique sound of these early Sun recordings was Sam Phillips’ ingenious use of slapback echo. While other studios used echo chambers, Phillips devised a simple yet effective system using two tape recorders: one to record the live sound, and a second that simultaneously played the sound back a fraction of a second later into the same room, where the first recorder picked it up again, creating a distinctive, tight echo effect, particularly noticeable on the vocals. This technique became a hallmark of the Sun sound and was widely imitated (often poorly) as artists who started at Sun moved to larger labels.

With the record pressed, Phillips took it to his friend, Memphis DJ Dewey Phillips (no relation). Dewey, known for playing R&B music for a primarily Black audience on his show “Red, Hot and Blue,” played “That’s All Right, Mama.” The response was immediate and overwhelming. Listeners called in repeatedly to request the song. Elvis, so nervous he went to the cinema to avoid hearing it, was reportedly dragged out by his mother to come to the radio station for an on-air interview. Dewey, strategically, asked Elvis what high school he attended, a subtle way to signal to his listeners that the singer was white, as many had assumed from the sound and the radio show’s format that he was Black.

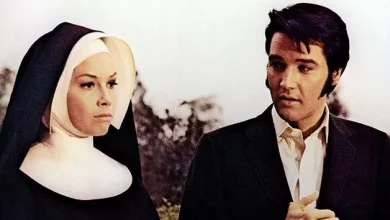

The song was a hit, at least locally, considering it was a country-leaning record released on a blues label. This success led to their first significant live performance. It was at this crucial early live show that Elvis’s legendary stage persona began to form, somewhat unexpectedly due to his nervousness. As Scotty Moore often recounted, Elvis was incredibly shy and his legs would literally shake when he was on stage. Wearing his characteristic baggy trousers (a style favored by Black men at the time), this nervous shaking didn’t look like fear; instead, it created a dynamic, visually arresting movement that audiences, particularly young women, found electrifying and overtly sexual.

The crowd’s wild reaction to his involuntary leg movements wasn’t lost on Elvis. He quickly learned to channel and exaggerate these movements, transforming crippling stage fright into a magnetic, dynamic stage presence. The shy, awkward boy with the spotty neck, who had struggled to fit in, had found a way to connect with and electrify an audience simply by amplifying his own nervous energy. This interaction between artist and audience in those early performances is a key part of the story of elvis presley that’s alright mama live.

From this blend of blues, country, gospel, and pop sensibilities, filtered through Sam Phillips’ unique production and Elvis’s raw, uninhibited delivery and evolving stage presence, a new musical force was born. “That’s All Right, Mama” wasn’t just a song; it was the sound of boundaries being blurred, the sound of the past giving way to the future, and the sound that launched the career of the man who would become the King of Rock and Roll. Understanding its origins helps us appreciate the accidental genius and cultural collision that defined early rock and roll. For more on his recorded output, explore this presley songs list.

The path from a nervous studio session and a shaky first public performance to global superstardom was rapid and unprecedented. The immediate, visceral reaction to “That’s All Right, Mama,” both on the radio and on stage, signaled that Elvis Presley was fundamentally different from anything listeners and audiences had experienced before. His ability to embody and perform this new hybrid sound, combined with a captivating and increasingly confident stage presence born from initial awkwardness, set the stage for his explosive rise. The story of it’s alright elvis – the song that announced him to the world – is the story of how an unlikely combination of factors converged at Sun Records to change music forever.