The Profound Journey Behind Elvis Presley Singing ‘An American Trilogy’

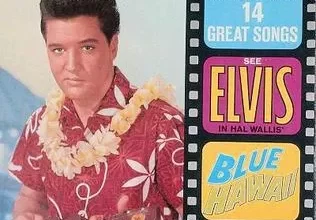

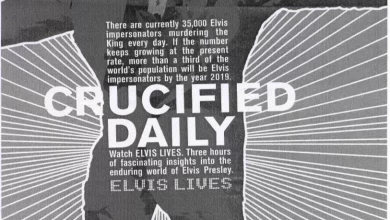

In 1972, the King of Rock and Roll, Elvis Presley, was redefining his legendary Las Vegas residency. He was adding new songs and visual elements like his signature cape. Facing personal changes, including his separation from Priscilla, Elvis reportedly felt he was “past the age of Christ crucified.” The raw power of his ’68 Comeback Special felt like a distant memory, and his classic hits, while beloved, were beginning to sound… like old hits. If redemption or reinvention was possible, Elvis, as always, would seek it through the transformative power of music. This era saw the emergence of a song that would become an iconic staple of his live performances: “An American Trilogy.” The story behind Elvis Singing American Trilogy is a deep dive into the complex soul of American music and history.

At the heart of “An American Trilogy” lies a unique blend of three distinct musical pieces, each carrying its own significant, and at times controversial, history. To understand the trilogy, one must first look to the origins of some of America’s earliest popular music forms, including minstrelsy.

The Roots of American Music: A Complex Heritage

For better or worse, minstrel music represents an original vein of American popular music. Born from comic sketches where white performers in blackface caricatured Black individuals through jokes, songs, and dances, these sketches evolved into full touring shows. While the humor was often vicious, perpetuating harmful stereotypes of laziness and simple-mindedness, it’s undeniable that minstrelsy drew, albeit offensively, from Black cultural forms and became a significant part of the American entertainment landscape. Understanding this difficult history is crucial to tracing the lineage of blues, jazz, country, and eventually, rock and roll.

One of the best-known early minstrel songs is “Dixie.” Likely written by Ohioan Daniel Decatur Emmett in the 1850s, the song is purportedly from the perspective of a freed slave longing for his southern plantation days. Its original lyrics, written in exaggerated dialect, are a compilation from other songs, resulting in a narrative that is historically and thematically messy. The original sheet music, reflecting the common practice of the time, included lines like:

I wish I was in de land of cotton,

Old times dar am not forgotten;

Emmett was also known for writing songs like “Turkey In The Straw” and Abraham Lincoln’s favorite, “Blue-Tail Fly.”

The history of “Dixie” is deeply problematic. Its origins are steeped in the racist caricatures of minstrelsy, presenting an absurd image of Black individuals yearning for slavery. Yet, the song’s meaning and cultural resonance have shifted dramatically over time. During the Civil War, it was adopted as a powerful anthem by the Confederacy, transforming from a lighthearted (though offensive) minstrel tune into a symbol of a cause. It became further entrenched in Southern white culture, sometimes sung defiantly in response to Civil Rights anthems like “We Shall Overcome.”

However, for younger generations unfamiliar with this fraught history, “Dixie” sometimes morphed into a seemingly sweet, timeless melody evoking a simple longing for the beautiful Southland, stripped of its painful past. Despite its origins, the melody itself, when separated from its original racist lyrics and context, has been argued to express a universal human feeling of estrangement or being out of place, a desire for simpler times, whether they ever truly existed or not.

Both Mickey Newbury, the song’s composer, and Elvis Presley grew up in the American South, where “Dixie” and its complex legacy were deeply embedded in the cultural landscape. The South holds a unique, often romanticized, view of its history. As William Faulkner famously said, “The past is not dead, it is not even past.” The South remains a place where immense pride and profound shame are intertwined, much like powerful rivers converging.

From Revival Hymn to Union Anthem

The second component of “An American Trilogy” traces its roots back to a different vein of American music: revival hymns. In 1855, William Steffe edited and wrote down a hymn titled “Canaan’s Happy Shore”:

(Verse)

Say, brothers, will you meet us

Say, brothers, will you meet us

Say, brothers, will you meet us

On Canaan’s happy shore(Refrain)

Glory, glory, hallelujah

Glory, glory, hallelujah

Glory, glory, hallelujah

For ever, evermore!

This melody quickly gained popularity. In 1860, Thomas Bishop wrote a new set of lyrics to the tune, creating a marching song for his Massachusetts Infantry called “John Brown’s Body.” This song honored the abolitionist John Brown, who in 1859 attempted to spark an armed insurrection against slavery and was subsequently hanged for treason. Brown remains a controversial but pivotal figure in American history, seen variously as a fanatic, a martyr, and a catalyst for the Civil War. Malcolm X even referenced him when asked about white participation in the Organization of Afro-American Unity.

Bishop’s lyrics for “John Brown’s Body” connected the powerful melody to the abolitionist cause:

(Verse)

John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave

John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave

John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave

His souls is marching on!(Refrain)

Glory, glory, hallelujah

Glory, glory, hallelujah

Glory, glory, hallelujah

His souls is marching on!

A year later, in November 1861, the abolitionist, activist, and poet Julia Ward Howe heard Union soldiers singing “John Brown’s Body.” Inspired, she feverishly rewrote the words, creating what became the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” This version, filled with powerful biblical imagery, transformed the marching tune into a soaring anthem for the Union cause, framing the Civil War as a divine struggle for freedom.

(Verse)

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword

His truth is marching on(Refrain)

Glory, glory, hallelujah

Glory, glory, hallelujah

Glory, glory, hallelujah

His truth is marching on

The Thread of Hope: “All My Trials”

The third and final piece woven into Mickey Newbury’s composition is the refrain from an old Bahamian lullaby, “All My Trials.” This song, popularized by the folk revival movement of the 1950s and 60s, carries a different kind of weight – one of endurance, suffering, and the unwavering hope for a better future.

All my trials, Lord

Soon be over

This simple refrain taps into a profoundly human, and particularly American, spiritual idea: the concept of enduring hardship in the present with the steadfast belief that things will eventually improve, whether in this life or the next.

Mickey Newbury’s Synthesis: Forging the Trilogy

Mickey Newbury masterfully combined these disparate elements into “An American Trilogy.” He took the melancholic longing often associated with “Dixie,” the soaring, triumphant spirit of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” (using the “Glory, Hallelujah” melody), and the quiet, enduring hope of “All My Trials.” Newbury didn’t just string the songs together; he crafted a narrative arc, moving from a sense of past or present loss towards ultimate spiritual triumph and hope. This composition, representing North, South, and a universal human yearning, became a powerful, albeit complex, musical tapestry reflecting the American psyche – a “melting pot” of diverse experiences, beliefs, joys, and sorrows.

American culture is founded on the idea of tomorrow being better, the land of opportunity. Even amidst difficulties, there’s the persistent dream of improvement. This inherent optimism, intertwined with the recognition of struggle, is powerfully captured in the trilogy’s structure and lyrical fragments. For more on significant songs from Elvis’s career, explore this [list of Elvis Presley songs].

The Impact of Elvis Singing ‘An American Trilogy’

When Elvis Presley first heard Mickey Newbury’s recording, it reportedly struck him deeply. In 1972, facing personal turmoil and performing for audiences grappling with the complexities of the Vietnam War and social upheaval, the song resonated profoundly. It wasn’t just a performance; it felt like a prayer, a plea for something better, a musical expression of the collective need for hope in a turbulent era.

Elvis sang “An American Trilogy” not just with his voice, but with his whole being. He performed it as a man holding onto a life preserver, pouring his own vulnerability and the audience’s shared anxieties into the performance. He made it a centerpiece of his shows, leaving arenas with the powerful melody and message ringing in people’s ears – audiences who needed to hear it from an artist who needed to sing it. His performance elevated the song from a thoughtful composition to a cultural phenomenon, making Elvis Singing American Trilogy a powerful symbol of his later career and its connection to the American spirit.

While some might view the song, with its dramatic arrangement and historical components, as antiquated or even “cheesy,” its enduring power for many lies precisely in its earnestness and its ability to connect with fundamental human emotions. It forces a confrontation with difficult histories while simultaneously offering a path toward unity and hope. For fans looking into his extensive performance history, exploring details like [Elvis’s “Burning Love” with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra] or songs from his movies such as [elvis presley change of habit songs] provides further context to his evolving artistry during this period.

The song sparks varied reactions, reflecting the complex histories it embodies. Some listeners may struggle to move past the problematic origins of “Dixie,” focusing on the scars of American history. Others find deep truth in its message of hope and overcoming trials, echoing the “glory hallelujah” spirit. This duality is perhaps the most American thing about the trilogy itself.

Conclusion

Elvis Presley’s interpretation of “An American Trilogy” became far more than just another song in his setlist. It was a powerful cultural statement, a musical reconciliation of disparate historical narratives, and a poignant expression of hope during a time of uncertainty. By weaving together a controversial Southern folk song, a triumphant Union anthem, and a hopeful spiritual, Mickey Newbury created a work that Elvis delivered with raw emotion and gravitas. The enduring legacy of elvis singing american trilogy lies in its ability to provoke thought, acknowledge complexity, and ultimately, offer a message of unity and resilience that continues to resonate with audiences worldwide.