The Raw Power of the Hound Dog Song: Big Mama Thornton’s Original Story

Welcome to a deep dive into the history of rock music, where we often find the roots of legendary tracks buried beneath layers of later fame. One such iconic tune is the Hound Dog Song. While most famously associated with Elvis Presley, its true origin story, and perhaps its most potent rendition, belongs to the powerful blues shouter Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton. Her version predates the King’s by several years and carries a raw energy and complex narrative that is essential to understanding the song’s journey and impact on American music history.

The story of the Hound Dog Song and its emergence in the 1950s is intertwined with the complicated racial landscape of America during that era. The development of early rock and roll often occurred in the liminal spaces, the borders between the culturally imposed categories of “Black” and “white.” These categories, essentially arbitrary binaries, didn’t neatly fit many people, and the 1950s saw these lines being redrawn. This created unique spaces where interesting art could flourish at the boundaries, often involving collaborations across racial and ethnic lines that were unusual for the time. It’s crucial to note that exploring this context is about acknowledging the distortions caused by racism, not endorsing them, but understanding how they shaped the cultural landscape.

The music industry reflected these complexities. People who didn’t fit neatly into the Black/white binary, like Jewish people or Greek-Americans who chose to identify with Black culture, often became facilitators in the burgeoning rhythm and blues and rock and roll scenes. They were “white enough” to access financing and navigate the dominant industry structures but also identified with or were deeply involved in Black music and culture. This positioning allowed them to bring white money and industry connections to Black artists who were often exploited by the mainstream system.

Willie Mae Thornton’s Unforgettable Presence

Willie Mae Thornton, later known as Big Mama Thornton, was a force of nature. Big in stature (reportedly weighing 350 pounds) and big in voice, she often claimed she didn’t need a microphone. She embodied the power of a blues shouter, a role typically associated with men, with a vocal intensity that matched or exceeded any male counterpart.

Her journey into music began at fourteen under the mentorship of singer “Diamond Teeth Mary,” who performed constantly until her death at ninety-seven and was the half-sister of blues legend Bessie Smith. Mary, known for the diamonds embedded in her front teeth for stage presence, discovered young Willie Mae singing while working on a garbage truck. Mary, who had run away from an abusive home as a teen and joined the circus dressed in boy’s clothes, likely saw a kindred spirit in Willie Mae, a girl who only wore boy’s clothes herself.

Thornton spent roughly a decade with Diamond Teeth Mary’s revue, sharing stages with future stars like Little Richard. This environment, though tied to less-than-respectable enterprises like brothels run by the manager, was a vital training ground for a young entertainer, teaching her to command a stage quickly. Being a female blues singer in the 1940s was challenging, especially if one didn’t fit conventional standards of attractiveness or societal expectations regarding sexuality or gender identity. Thornton didn’t fit neatly into these boxes. Accounts of her are varied; some described her as potentially bisexual or uninterested in men or women, while others even speculated she might have been trans (though she used she/her pronouns throughout her life).

Her persona could be intimidating; she reportedly had razor scars on her face and favored a potent (and dangerous) drink mix of embalming fluid and grape juice. Yet, while others often put her in the box of an “angry, aggressive black woman,” she pushed back against this caricature. She corrected stories of her fighting promoters, saying, “I never did fight the promoters. All I ever did was ask them for my money. Pay me and there won’t be no hard feelings.” And regarding her appearance, while often called “masculine-looking,” she stated simply, “I don’t go out on stage trying to look pretty. I was born pretty.” Much of the public narrative around Thornton came from external impressions, often filtered through the perspectives of men, rather than her own voice. Those who knew her well described her as intelligent, kind, charming, and funny, suggesting a more complex, perhaps vulnerable person underneath the outward swagger, possibly using substances to cope with a difficult life.

Life was indeed hard. After leaving the Harlem Revue due to being cheated out of money, she settled in Houston, Texas, building an audience while supplementing her income by shining shoes and sometimes sleeping in all-night establishments because she couldn’t afford rent. She had a child in her teens, but due to poverty, she was deemed an unfit mother, and the child was taken away.

In Houston, she began working with Don Robey, who ran Peacock Records and the Bronze Peacock Club. Robey had a mixed reputation, often praised by artists but notorious for stealing from songwriters. He was also known as a tough character, though Little Richard claimed Robey was too afraid of Thornton to physically intimidate her. Thornton recorded several singles for Peacock, but her style didn’t initially mesh well with the smoother Texas blues sound the label often produced.

The Johnny Otis Connection

Things changed when Don Robey acquired Duke Records and began working with bandleader, producer, and facilitator Johnny Otis. Otis came to Texas, striking a deal with Robey to audition and incorporate talented but commercially unsuccessful artists from Peacock and Duke, like Thornton, into his Johnny Otis Revue. Otis would produce their records in Los Angeles with his band, and Robey would release them.

Not all artists found success through this arrangement (Little Richard’s early recordings with Otis were an artistic dead-end for him, although he later found massive success). But for Willie Mae Thornton, something clicked. She and Otis became lifelong friends and collaborators. Otis was the first to encourage her to play harmonica. Her debut performance with the Johnny Otis Revue, singing Billy Ward and the Dominoes’ “Have Mercy Baby,” caused such a sensation that she had to be placed at the top of the bill. With this newfound prominence came a new stage name, courtesy of Otis, who had a knack for branding artists: Willie Mae Thornton became “Big Mama” Thornton.

Leiber and Stoller Enter the Scene

Johnny Otis, positioned on the border between white and Black culture, excelled at bringing people together. In 1952, he connected Big Mama Thornton with two young, white Jewish songwriters who were just starting their legendary careers: Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. Both teenagers had moved to California and had a deep passion for Black American music, albeit from different angles.

Mike Stoller was a trained musician with interests ranging from modern jazz (Thelonius Monk) and classical (Bartok) to stride and boogie-woogie. He had even studied with the influential jazz pianist James P. Johnson, learning the rudiments of blues piano, including the crucial boogie bassline. Jerry Leiber was a blues fanatic whose ambition to become a songwriter solidified after hearing Jimmy Witherspoon’s “Ain’t Nobody’s Business if I Do.” He started writing lyrics, even penning “Real Ugly Woman,” which Witherspoon would later record.

Their paths crossed when Leiber, working in a record store, met Lester Sill, a national sales manager for Modern Records, a small blues label. Sill, impressed by Leiber’s enthusiasm for blues and his songwriting aspirations, encouraged him to find a musical partner. A mutual friend introduced Leiber to Stoller. Initially skeptical that “songs” were the kind of pop tunes he disliked, Stoller’s interest ignited when he saw Leiber’s lyrics and realized they were blues. They began collaborating in 1950 and continued for the rest of Leiber’s life (Stoller is still active). Through connections like Lester Sill and Ralph Bass (who knew them from the East Coast and introduced them to Johnny Otis), they started writing for artists like Little Esther and The Robins, whose “That’s What the Good Book Says” was the very first single with a Leiber and Stoller writing credit.

The Creation and Recording of the Hound Dog Song

Working with Johnny Otis and artists like Big Mama Thornton felt like collaborating with heroes for the young Leiber and Stoller. When Otis asked if they had a song for Thornton, they quickly retreated to Stoller’s house and wrote “Hound Dog” in a style they believed would suit her powerful voice.

The term “hound dog” was contemporary Black slang for a gigolo or someone who loafs around, depending on women. Leiber and Stoller aimed for an aggressive song from a female perspective, dismantling such a man, incorporating sexual undertones (later amplified in Thornton’s follow-up, “Tom Cat”).

They had strong ideas about how Thornton should perform the song and made the mistake of trying to direct the seasoned blues veteran. When Jerry Leiber suggested she “attack it” rather than croon, Thornton famously responded by pointing to her crotch and saying, “attack this!” Johnny Otis, who was present, reportedly hit a rimshot after her retort, adding to the moment’s tension and humor. However, Otis then suggested Leiber sing it for her, and Thornton, after hearing his demonstration, agreed to try their approach. Once the communication barrier was overcome, Big Mama Thornton delivered what became the definitive performance of the original hound dog song.

The recording session for “Hound Dog” is also notable as one of the last times Johnny Otis played drums on a record. He had largely given up drumming due to difficulty holding sticks but could still play vibraphone. However, during rehearsals, he played drums with a distinctive style, turning off the snare. During the actual recording, the session drummer wasn’t capturing the feel Leiber and Stoller wanted, so they coaxed Otis into the studio to play the part as he had in rehearsal.

The Lingering Credit Dispute

What happened with the songwriting credits for the hound dog song remains a subject of debate. Everyone agrees that Otis was credited as a co-writer early on, but the credit later reverted solely to Leiber and Stoller. Otis claimed he significantly helped structure and rewrite the song, removing what he considered “derogatory crap” and stereotypical references (like chicken and watermelon) that Leiber and Stoller initially included, and that he did the arrangement. He alleged Leiber and Stoller acknowledged his co-writing role until Elvis Presley decided to record the song.

Leiber and Stoller disputed this, claiming Otis had no hand in the songwriting and had misrepresented himself to Don Robey, falsely claiming power of attorney and co-writing credit to defraud them. Ironically, it was reportedly Otis who initially ensured Leiber and Stoller received any credit at all, as Don Robey, known for stealing credits, initially listed himself and Thornton as the writers.

Regardless of the precise truth, Leiber and Stoller have held the sole songwriting credits for over sixty years, and Otis never legally challenged their claim. Despite this, there didn’t seem to be deep animosity, with parties often praising each other’s talents, though Otis lamented the lost income: “I could have sent my kids to college, like they sent theirs. But, oh well, if I dwell on that I get quite unhappy, so we try to move on.”

The Song’s Famous Trajectory

Big Mama Thornton’s version of the hound dog song was a massive hit, selling over a million copies. However, the financial rewards were minimal for her and initially for the songwriters. Thornton reportedly received a flat fee of $500. Leiber and Stoller received a check for $1,200, which bounced. This experience led them to form their own record label with Lester Sill, a move that would be significant for their future careers.

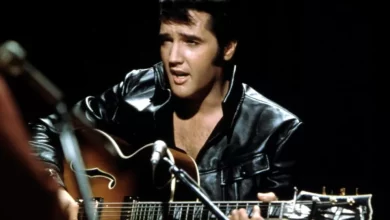

The version that propelled the hound dog song into global consciousness was Elvis Presley’s. Interestingly, Elvis’s iconic recording was not a direct cover of Big Mama Thornton’s blues original. Instead, it was based on a version by a white Las Vegas lounge act, Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, which was essentially a playful parody of Thornton’s powerful rendition. This version smoothed out some of the raw edges and lyrical nuances of Thornton’s performance. You can explore the history specifically behind the elvis hound dog version further. The story of the hound dog presley connection is a fascinating chapter in music history.

Big Mama Thornton never achieved the sustained mainstream success her talent deserved. She later wrote the song “Ball and Chain,” which became a major hit for Janis Joplin. Listeners familiar with Joplin’s version can clearly hear how much she drew from Thornton’s vocal style and intensity. Yet, due to a bad contract, Thornton never received royalties from her own composition, a far greater injustice in her view than the fact that Elvis had a hit with “Hound Dog” (a song she didn’t write, and for which the writers were paid, albeit belatedly). Discussing popular songs associated with Elvis, other notable tracks include elvis song jailhouse rock and the touching ballad song old shep by elvis presley. For more general information, there are many fascinating stories about song about elvis.

Thornton continued performing until just days before her death in July 1984, significantly thinner but still driven by her passion for music. Like her friend Little Esther, who died two weeks earlier, she asked Johnny Otis (by then Reverend Johnny Otis) to deliver her eulogy. Otis’s words captured the essence of her struggle and spirit: “Mama always told me that the blues were more important than having money. She told me: Artists are artists and businessmen are businessmen. But the trouble is the artist’s money stays in the businessmen’s hands. […]. Don’t feel sorry for Big Mama. There’s no more pain. No more suffering in a society where the color of skin was more important than the quality of your talent.”

Conclusion

The history of the hound dog song is a microcosm of the American music industry in the mid-20th century – a blend of groundbreaking artistic creation, complex cultural dynamics, controversial business practices, and the often-unequal distribution of fame and fortune. While Elvis Presley’s version became a cultural phenomenon, it is Big Mama Thornton’s original recording that stands as the raw, powerful source. Her struggles and triumphs highlight the challenges faced by Black artists, particularly Black women, in a prejudiced society and industry. The legacy of the hound dog song is incomplete without acknowledging the indomitable spirit and talent of Big Mama Thornton, the artist who first unleashed its full, untamed power.