The Strongest Military in the World 2021: US Strategy Analysis

This analysis delves into the strategic context, budget implications, and force structure plans shaping the United States military in fiscal year (FY) 2021. As global dynamics shift, understanding the components of U.S. military power—its composition, readiness, modernization efforts, and sustainment capabilities—is crucial, particularly in evaluating its position relative to the concept of The Strongest Military In The World 2021. The Department of Defense (DOD) defines force structure as “the number, size, and structure of units,” a key element alongside readiness, modernization, and sustainment. This examination, drawing from CSIS Senior Adviser Mark Cancian’s research, explores the Trump administration’s strategy and budget decisions for FY 2021, the resulting trade-offs, long-term challenges, and the potential impact of external factors like the Covid-19 pandemic on maintaining military preeminence.

The Strategic Context: Trump Administration’s Approach

Any analysis of military force structure must begin with the overarching strategy. The Trump administration’s national security policy, articulated in the National Security Strategy (NSS) of December 2017 and the National Defense Strategy (NDS) of January 2018, provides the framework for understanding its force planning for FY 2021.

National Security and Defense Strategies (NSS/NDS)

The NDS presented a stark assessment, suggesting the U.S. military’s competitive edge was eroding against potential adversaries. It called for “increased and sustained investment” to address “long-term strategic competitions with China and Russia.” Key strategic points included:

- Five Threats: Identifying China, Russia, North Korea, Iran, and global terrorism as primary threats. Notably, China was placed first, signifying a shift in emphasis compared to the previous administration which prioritized Russia. The strategy distinctly focused on great power competition with China and Russia.

- Importance of Allies: Despite presidential rhetoric that sometimes appeared critical, the NDS officially stressed the value of alliances and the need for these partnerships.

- Management Reform: Emphasizing the need for efficiency and responsible use of taxpayer funds, particularly during periods of defense budget increases.

A significant shift occurred in the force sizing construct. The long-standing “two major conflict” model was replaced by a “1+” construct, designed to handle defeating aggression by one major power while deterring another. This change acknowledged the heightened demands of potential conflict with peer competitors like China or Russia compared to past regional conflicts. The specific implications for force planning remained somewhat ambiguous in unclassified documents.

Overall, the NSS and NDS conveyed a strong commitment to U.S. primacy, stating the DOD’s goal to “remain the preeminent military power in the world, ensure the balance of power remains in our favor, and advance an international order that is most conducive to our security and prosperity.” The objective was clear: “prevail in conflict and preserve peace through strength,” with no indication of accepting a diminished global status.

Budget Realities: Funding the Strategy

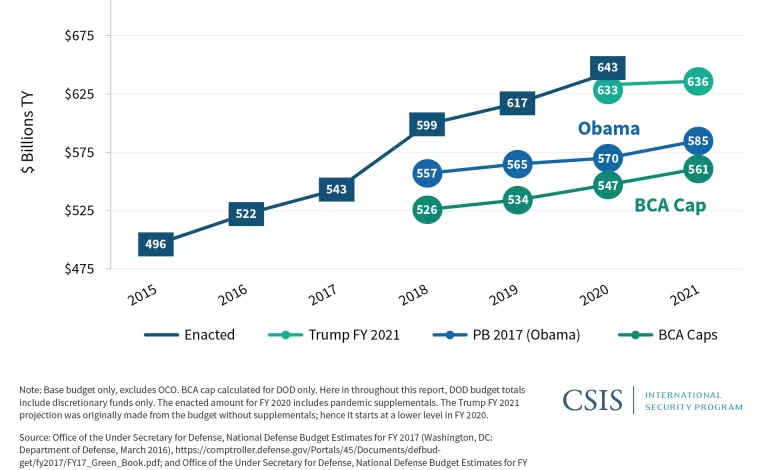

Strategy requires resources. The Trump administration initially backed its strategic objectives with increased funding. Defense budgets from FY 2017 to FY 2020 surpassed the limits set by the Budget Control Act (BCA) and exceeded the levels planned by the Obama administration. These increases enabled the military services to focus on rebuilding readiness, launching robust modernization programs, and achieving modest growth in force structure.

FY 2021 Budget Trade-offs

However, the period of budget growth ended with the FY 2021 proposal. Flat or declining budgets necessitate difficult choices between readiness, modernization, and force size. The FY 2021 budget reflected these trade-offs.

Active component end strength saw a slight planned increase, rising from 1,346,000 in FY 2020 to a projected 1,351,500 in FY 2021. Reserve component end strength remained largely static, projected at 802,000 for FY 2021, an increase of only 100 personnel from FY 2020. This stability, even amidst budget constraints, likely stemmed from lingering expansion plans, inherent difficulties in reducing personnel, and persistent high demand for deployed forces.

Readiness levels achieved in previous years were generally maintained, according to publicly available metrics like flying hours and ship steaming days, and supported by service statements regarding classified readiness assessments. The department asserted it was on track with its Readiness Recovery Framework, though specifics remained undisclosed.

Sustaining readiness occurred despite a $4.5 billion reduction in the base budget’s operations and maintenance (O&M) funding. While future O&M projections indicated declines, historical trends show this account typically grows faster than inflation, making future projections uncertain.

A significant uncertainty for readiness was the long-term impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. Initial shutdowns of training and recruitment in Spring 2020 created unsustainable conditions. While activities resumed with precautions, reports suggested that not all planned training for 2020 could be executed, potentially affecting long-term readiness if disruptions continued.

Modernization faced the most significant pressure. Total funding for procurement and research, development, testing, and evaluation (RDT&E) decreased by $4.8 billion nominally ($9.8 billion in constant dollars) in FY 2021. Projections over the five-year defense program showed procurement dipping and then recovering, but RDT&E funding declining substantially. This trend raised concerns about the ability to develop and field the advanced systems required by the NDS in sufficient numbers.

US Force Structure Plans for FY 2021

The FY 2021 budget demonstrated that even with prior increases, substantial growth in force structure was limited. Force size appeared to be a lower priority compared to readiness and modernization under the NDS framework. Table 2 illustrates the evolution of force structure targets compared to previous benchmarks and aspirations.

The table compares the FY 2021 plan against potential forces under BCA caps (widely considered inadequate), the final Obama administration plan, and the larger force structure advocated by President Trump during his campaign (based on Heritage Foundation recommendations). The FY 2021 plan showed only modest increases over the Obama levels, falling far short of the campaign goals.

Long-Term Force Structure Outlook (FY 2025 Projections)

Detailed long-term force structure plans have become scarce in DOD budget documents, possibly due to concerns about revealing information to adversaries. However, available end strength projections offer some insight.

Projections indicated a small active component end strength increase of about 15,100 personnel (1.1 percent) between FY 2021 and FY 2025, reaching 1,361,000. Growth was anticipated in the Army and Navy, while the Air Force and Marine Corps were projected to decrease slightly.

Reserve components showed even smaller growth, increasing by roughly 4,300 personnel (0.5 percent) over the same period. Army and Air Force reserves were projected to grow, the Marine Corps reserve to remain steady, and the Navy reserve to continue its decline.

While end strength doesn’t fully capture force structure (unit composition and equipment), these trends suggested a prioritization by the services to protect personnel numbers, potentially at the expense of modernization, despite the NDS’s stated priorities.

Major Challenges Facing US Force Structure

Looking ahead, U.S. force structure faces several significant challenges and a major uncertainty.

Challenge 1: Persistent Global Demands

The U.S. military confronts continuous demands for crisis response, allied engagement, managing “gray zone” competition, and handling ongoing regional conflicts. This high operational tempo, described by one observer as a “bear trap of current commitments,” works against efforts to reduce force size. Many experts argue that physical presence is essential for global leadership and addressing these varied threats, warning against focusing solely on future high-end conflicts (“next war-itis”). Conservative think tanks like the Heritage Foundation and the American Enterprise Institute have argued for significantly larger force structures to meet these combined demands, often rating current forces as deficient in capacity. The tension between preparing for great power conflict and meeting daily demands pushes towards a “high-low mix” of capabilities, incorporating both advanced systems and less expensive platforms suitable for less demanding scenarios – an approach seemingly reflected in some service procurement decisions (e.g., retaining A-10s, buying F-15EXs, pursuing frigates).

Challenge 2: The Strategy-Resources Gap

A persistent gap often exists between strategic ambitions and available resources. With defense budgets projected to be flat or potentially declining after FY 2020, this gap becomes more acute. The NDS prioritizes readiness and modernization, making force structure the likely area to face cuts if resources tighten. Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Dunford, repeatedly stated that the defense strategy required 3-5 percent real budget growth annually to be fully resourced.

Compounding this, historical analysis shows that military personnel compensation and O&M costs tend to rise faster than general inflation, putting further pressure on budgets just to maintain current capabilities. While DOD aims for savings through efficiencies and reforms, achieving substantial savings from overhead cuts has proven difficult (e.g., inability to secure base closures). Critics, including the National Defense Strategy Commission and conservative think tanks, have warned that inadequate resources put the U.S. near “strategic insolvency.” A potential Biden administration, with platform language suggesting budget cuts (“maintain a strong defense…for less”), could potentially widen this gap further, although specific plans remained unclear.

Challenge 3: Shifting to Great Power Conflict

A common criticism is that despite the NDS, budgets haven’t shifted aggressively enough away from “legacy” forces towards the advanced capabilities needed for great power competition with China and Russia. Critics advocate cutting existing force structure to fund more rapid modernization. The definition of “legacy” is central to this debate. Strategic critics often view legacy systems as types of platforms based on older operational concepts (e.g., manned aircraft, large carriers, traditional armored vehicles), favoring smaller, unmanned, distributed systems. The military services, however, tend to define legacy as specific older systems within a platform type, preferring to retire older models (like F-16s or old cruisers) to buy newer versions of similar systems (like F-35s or new destroyers). Implementing a strategy heavily focused on modernization under constrained budgets could lead to significant force structure reductions, potentially driving numbers down towards levels previously associated with sequestration.

Challenge 4: Alternative Strategy Proposals

The NDS, while broadly supported, faces challenges from alternative strategic viewpoints advocating for less U.S. military involvement overseas and reduced defense spending. Libertarian perspectives, represented by organizations like CATO, argue for a strategy of “restraint,” reducing forward deployments and significantly cutting Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps force structure (by roughly a third), while maintaining a capable Navy for global reach when needed. Similarly, progressive critiques propose deep cuts, focusing on ground forces, readiness reductions via civilian/contractor cuts, and terminating nuclear modernization and missile defense programs. Such alternative strategies, if adopted, would fundamentally alter the size and composition of the U.S. military.

Public Opinion and the Future Force

Ultimately, public support shapes long-term defense policy. Polling data indicates nuanced public opinion. While very few Americans believe the U.S. military is “too strong,” support for increased defense spending or force expansion is generally weak. The perception that the military is “not strong enough” rose after 2012 but decreased after 2017, perhaps reflecting satisfaction with budget increases under Trump or concerns about his administration.

Regarding America’s global role, the public generally supports NATO membership and considering allies’ interests but is divided on whether the U.S. should be more or less involved in world affairs. This suggests public backing for maintaining a capable defense but potential resistance to major spending increases or overly interventionist policies.

The COVID-19 Wild Card

The Covid-19 pandemic emerged as a major disruptive force with uncertain long-term consequences for national security. While DOD initially managed the health crisis relatively well within its ranks compared to the general population, the pandemic’s economic fallout and societal impact raised questions about future defense budgets. Some speculated that the massive increase in national debt and focus on domestic recovery could lead to reduced defense spending, a sentiment echoed by some progressive groups in Congress. Secretary Esper himself acknowledged concerns about potentially smaller future budgets.

Conversely, the pandemic highlighted vulnerabilities and shifted public threat perceptions, with infectious disease surging as a top concern. This could potentially drive efforts to enhance DOD’s role in pandemic response and biodefense, possibly involving expanded medical research, dual-use capabilities (like hospital ships), or rethinking planned cuts to the military medical community. Whether expanding DOD’s role in domestic emergencies is appropriate remains debatable, given existing civilian agencies and the military’s preference for focusing on warfighting missions. However, DOD’s capabilities often lead to its involvement in national crises. The pandemic remains a wild card, potentially influencing budget priorities, strategic focus, and the very structure of U.S. forces in ways yet to be fully determined.

Conclusion

The analysis of U.S. military force structure for FY 2021 reveals a complex picture. While the administration aimed to maintain the nation’s status as arguably The Strongest Military In The World 2021 through its National Defense Strategy, budget realities forced trade-offs. Readiness gains were largely preserved and force size saw modest growth, but modernization efforts faced pressure. Looking forward, the U.S. military confronts significant challenges: balancing persistent global operational demands with the need to prepare for great power competition, navigating a likely strategy-resources gap exacerbated by flat or declining budgets, determining how aggressively to shift away from legacy systems, and contending with alternative strategic visions advocating for restraint. Superimposed on these is the uncertainty introduced by the Covid-19 pandemic, which could impact everything from budgets to mission priorities. Public opinion supports a strong defense but shows limited appetite for increased spending, adding another layer of complexity. The path forward requires navigating these competing pressures to sustain a military force capable of meeting diverse global challenges while adapting to a changing strategic and fiscal landscape.