Elvis and Ann Margret In Love: Could It Have Saved the King?

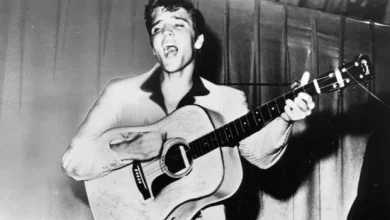

The history of rock and roll is filled with legendary figures and captivating stories, but few relationships spark as much “what if” speculation as that of Elvis Presley and Ann-Margret. Marty Lacker, a member of Elvis’ inner circle, once mused, “If Elvis had ended up with Thumper [his nickname for Ann-Margret], this whole story might have wound up differently.” As devoted Elvis fans and students of entertainment history, we often focus on documented events. Yet, the enduring question of whether Elvis And Ann Margret In Love could have altered the King’s tragic trajectory persists. This exploration delves into their intense connection, the reasons they didn’t marry, and the likelihood of a different outcome had they tied the knot.

To navigate this hypothetical scenario, we rely on key accounts, primarily Priscilla Presley’s Elvis and Me (1985) and Ann-Margret’s Ann-Margret: My Story (1994). While Elvis left no memoirs, insights from close associates like Marty Lacker, Billy Smith, George Klein, and others provide valuable perspectives on his feelings towards the two most significant women in his life during that era.

The King Meets His Match: Sparks Fly on Viva Las Vegas

When Elvis met Ann-Margret on the set of Viva Las Vegas in 1963, the chemistry was immediate and undeniable. Unlike Priscilla Beaulieu, whom Elvis met as a 14-year-old in Germany and sought to mold into his ideal partner, Ann-Margret was already a force to be reckoned with. At 22, she was a rising Hollywood star, fresh off the success of Bye Bye Birdie, exuding confidence and worldliness. Elvis couldn’t shape her; he had to accept her as she was, a challenge he seemed eager to embrace initially.

Their connection went far beyond professional collaboration. They shared passions and personalities in a way that suggested a deeper compatibility.

“Soul Mates”: Understanding Their Deep Connection

Ann-Margret herself described the profound bond they formed. “The more time Elvis and I spent together, the more we learned how eerily similar we were,” she wrote in her autobiography. “Some things were obvious, such as a love of motorcycles, music, and performing. We’d both also experienced meteoric rises in show business; we liked our privacy; we loved our families; we had a strong belief in God.”

Their similarities fostered an intense intimacy. Ann-Margret elaborated: “We were indeed soul mates, shy on the outside, but unbridled within. We both lived on the edge and we both were self-destructive in our own ways… In many ways, both of us, despite fame and whatever else we’d achieved so quickly, had remained very childlike, and emotionally dependent. We wanted to find that same nonjudgmental, unqualified love that our parents gave us.” This description paints a picture of two individuals who truly understood each other on a fundamental level.

A Stark Choice: Ann-Margret vs. Priscilla

While Elvis was deeply involved with Ann-Margret, his prior connection to Priscilla loomed large. He had met Priscilla in 1959 when he was 24 and she was just 14. Her youth and perceived innocence appealed to him, offering a “blank slate” he could shape. By 1963, Priscilla was living at Graceland under Elvis’s strict control, managing her appearance, education, and social interactions according to his desires. “Whenever I stated my own opinions too strongly… he’d remind me that his was the stronger sex, and as a woman, I had my place,” Priscilla recalled, highlighting the power imbalance inherent in their relationship.

Ann-Margret represented the opposite: an established, independent woman with her own thriving career. Some in Elvis’s circle, like Billy Smith and Marty Lacker, believed it was a genuine dilemma for him, with Lacker even thinking Elvis might ultimately choose Ann-Margret. George Klein noted Elvis was “smitten with Priscilla” but also “honestly overwhelmed by the feelings he had for Ann-Margret.”

Why Didn’t Elvis Marry Ann-Margret?

Despite their profound connection, Ann-Margret stated they both recognized the impossibility of a future together early on. “His wish was that we could stay together,” she explained, “But of course we both knew that was impossible… Elvis and I knew he had commitments, promises to keep, and he vowed to keep his word.” This likely referred to his implicit or explicit promise to Priscilla.

They discussed marriage, acknowledging their compatibility. “Elvis didn’t like strong, aggressive women and I posed no threat there,” Ann-Margret mused, perhaps underestimating her own strength or Elvis’s complex desires. “He, on the other hand, was strong, gentle, exciting, and protective. Just the qualities I liked.” Yet, she maintained, “We were never engaged.”

Some insiders, like Lamar Fike, believed Ann-Margret’s career was the ultimate deal-breaker. Fike claimed Elvis would have married her “only if Ann quit the business,” adhering to a traditional Southern view of a wife’s role. Ann-Margret, fiercely dedicated to her hard-won career, wouldn’t agree. While Ann-Margret downplayed career conflicts in her book, Fike’s perspective highlights a potential major obstacle rooted in Elvis’s traditional values.

Lingering Feelings: A Love That Never Died?

The end of their official romance didn’t extinguish the flame. Both married others in May 1967 – Elvis to Priscilla, Ann-Margret to actor Roger Smith – but their connection endured. Ann-Margret recounts Elvis reaffirming his feelings on at least two occasions post-marriage.

In July 1967, shortly after their respective weddings, Elvis attended her Las Vegas show. Backstage, he dropped to one knee, took her hands, and “in a soft, gentle voice weighted by seriousness, he told me exactly how he still felt about me.” Five years later, in 1972, he visited her during a gathering in her Las Vegas hotel suite. Later that night, he phoned her room. “Saying he was lonely, he asked if he could see me,” she revealed. When she gently refused, explaining “You know I can’t,” Elvis replied, “I know, but I just want you to know that I still feel the same.” These moments suggest a deep, unresolved affection persisted long after their paths diverged.

The Hypothetical Marriage: Would It Have Lasted?

Returning to the core question: If Elvis had married Ann-Margret, could the marriage have survived, and could she have “saved” him? Despite their deep bond, the evidence suggests their marriage would have faced formidable challenges, making the second part of the question largely moot.

Firstly, the career issue, regardless of Ann-Margret’s public stance, likely would have created friction. Marty Lacker believed Elvis couldn’t handle seeing his wife in romantic scenes on screen: “He didn’t want to look up on a movie screen and see her in bed, kissing somebody. He couldn’t have handled it.” George Klein recounted Elvis’s unusual rudeness towards Steve McQueen in 1964, attributing it to McQueen’s steamy scenes with Ann-Margret in The Cincinnati Kid. If Elvis struggled with her on-screen romances as a girlfriend, it’s improbable he could accept them from a wife.

Secondly, and perhaps more decisively, Elvis’s persistent infidelity would have likely doomed the marriage. “Elvis never stopped seeing other women,” Lacker stated plainly. “Even when he was dating Ann-Margret.” Given their demanding careers requiring frequent separations, Elvis’s established pattern of womanizing makes it almost certain he would have been unfaithful. While Ann-Margret might have tolerated it during their affair, it’s difficult to imagine her accepting such behavior within a marriage.

Conclusion: A Fated Path?

The relationship between Elvis Presley and Ann-Margret remains one of Hollywood’s most compelling romantic narratives. They shared undeniable chemistry, profound similarities, and a deep, lasting affection that suggests Elvis And Ann Margret In Love was a genuine reality. However, contemplating the “what if” of marriage reveals significant hurdles. Conflicting career demands, Elvis’s traditional views on marriage, his jealousy, and his infidelity likely would have strained their union beyond repair.

Therefore, it seems improbable that a marriage between them would have endured long enough to significantly alter Elvis’s later life. Like Priscilla before her eventual departure, Ann-Margret would likely have found the constraints and infidelities of marriage to Elvis unbearable. Ultimately, Ann-Margret, despite their unique bond, was likely fated to watch from afar, alongside the rest of the world, as the man she deeply cared for succumbed to his demons. Their love story, though intense and real, seems destined to remain a poignant chapter rather than a life-altering alternate history.